Journey from Tezpur to Tawang

During this pandemic, the authorities are not allowing more than five passengers in a shared Sumo. However, none of the operators care about that rule in spite of charging nearly double the usual price for a trip. One of the reasons is that they are not able to get enough passengers to make a profit from the trip. The operators often club passengers who are headed for Dirang and other towns on the same route; that is exactly what happened with the four of us headed for Tawang—we had four more with us.

Kumar—our Sumo driver—stopped at various places to pick up passengers. This is how most of these shared Sumo services work. One has to book a seat ahead of time on phone and the driver picks them up at convenient points en route.

COVID-19 test is performed at Bhalukpong for people who are headed for Bomdila and Dirang while people headed for Tawang can have themselves tested at the Jang checkpost. Kumar stopped the the vehicle at the Bhalukpong checkpost and made the necessary entries. No one checked anything—neither our ILPs nor where we were headed. As such, the four passengers who got down at Dirang did not have to get themselves tested.

Arunachal is guarded by the military owing to its proximity as well as border dispute with China. Boarder Roads Organisation (BRO)—under the Ministry of Defense—maintains most of the arterial roads in Arunachal. We were stopped twice by BRO who were performing some maintenance work on the road. This set us back by an hour and a half. A fellow passenger was a jawan from the Indo-Tibetan Border Police battalion stationed at Dirang. He constantly nagged all of us about the delays. He had to report by 12:00 pm that day and was weary of the reprimand that he would receive from his superior if he was late. There was no way that we could have made it by then even if we hadn’t been stopped because of the ongoing maintenance works. Kumar didn’t care about him and neither did we. When his nagging had become irritable, all of us scolded him. It reduced the intensity of nagging but he didn’t fully stop. He even whined when we stopped for our breakfast at Bhalukpong. Later, when we stopped somewhere after Dirang for lunch, he wasn’t there and we were able to have our meals in peace.

The Sumo itself was very old with rust spots all over its body, including a corroded hole in the driver-side door. It’s radiator had heated up and fumes escaped from under the hoods. While climbing towards Sela pass, the car had a flat rear tire. There was a spare with us bus Kumar did not have a jack. We waited outside in the snow while Kumar stopped the next vehicle, borrowed a jack, replaced the tire, returned the jack, and restarted the Sumo. A spew of green antifreeze expelled out of the radiator. The radiator had dried up completely and the engine was hot. It was necessary to find a water source in order to proceed—something we encountered immediately after we had crossed the pass.

There was a possibility that a risk would materialise due to the delays. The COVID-19 test centre and the checkpost at Jang closed at 8:00 pm. If we reached there after their closure, we would have to sleep overnight in the car. Kumar assured us that if there weren’t any further delays, we would reach Jang between 6:00 pm and 7:00 pm. Fortunately, there weren’t any delays. It was 6:15 pm when we reached Jung. It was also very dark—even at the tents where a doctor and two nurses sat with test kits. After a swab-based Rapid Antigen Test that indicated that we were free of COVID-19 and an entry at the checkpost, we were all let go. They charged INR 250 per person for the test (except for an elderly senior citizen).

The Sumo dropped me at Old Market in Tawang at around 7:15 pm. Tenzing Gyatso—Phurpa’s friend, a lama in Tawang, and someone who shared his name with the current Dalai Lama—had already spoken to the owner of Hotel Samdrupling and had booked a room for me. Unfortunately, he had to leave for his village and I wasn’t able to meet him during my stay in Tawang.

It was hard to find any food at 7:30 pm in Tawang. Most shops usually open at 9:30 am. Utilities like salons, cobbler, etc. close by 5:00 pm, retail shops close by 6:00 pm, eateries by 7:00 pm while alcohol shops are usually open even at 8:30 pm. The only restaurant in Old Market whose signboard was lit at 7:30 pm was that of Gorichen. I bought some fried noodles and walked back to my hotel.

Tawang town

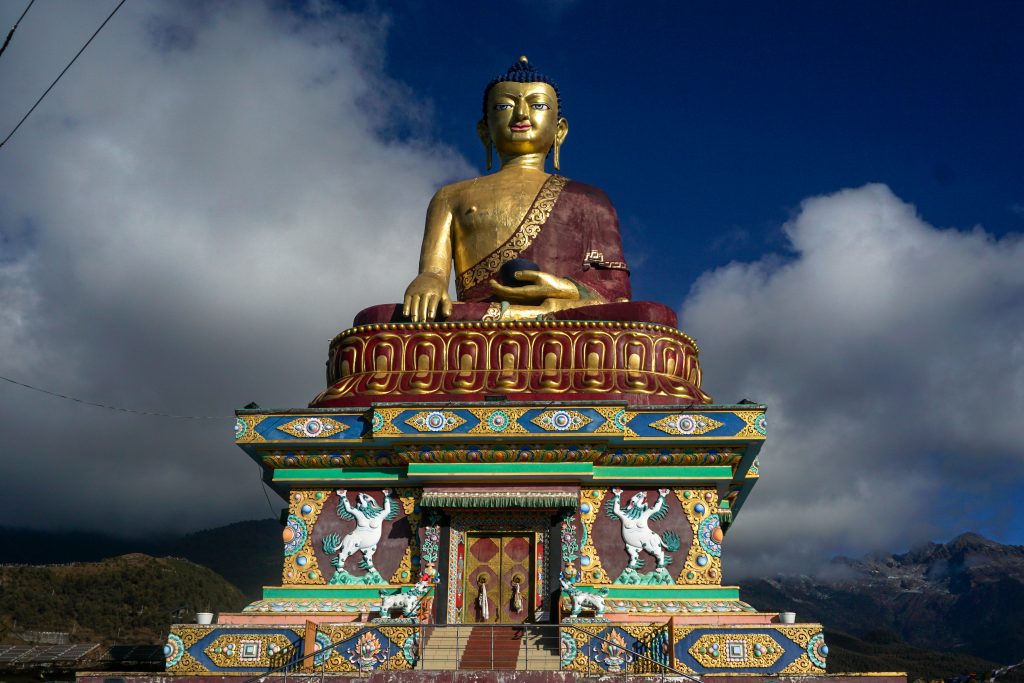

Tawang town comprises of a central administrative area and settlements surrounding three markets—Old Market, Nehru Market and New Market—and a vast area of land controlled by the military. A giant statue of Buddha above the Old Market looks over the valley. There are a number of villages surrounding the town—most of which are accessible by wide roads.

The roads in the Tawang Air Force Station—south-east to the city centre—and the barracks surrounding it is open to public as these motorable roads connect key civilian areas of Tawang. There is a helipad that is used not only by the military but also for the Tawang–Guwahati helicopter flights. While walking through the area, I encountered a transport helicopter that landed on the helipad from right over my head. The force of the air pushed by the rotors is strong enough to push someone off their feet.

Tawang War Memorial is right inside the military premises. Unfortunately, they didn’t allow me inside the memorial owing to the pandemic. While most tourist places in civilian jurisdiction had opened for the general public, the ones inside military campuses had not.

Tawang Monastery

The eponymous monastery is located in a south-west hill from Tawang. More precisely, this monastery—Tawang Galdan Namgye Lhatse (divine paradise chosen by horse)—is the namesake of the town and the district. It’s also one of the important monasteries in Tibetan Buddhism; specifically for the Gelug school to which the Dalai Lama belongs. It was established in accordance to the wishes of the fifth Dalai Lama. It would eventually serve his next incarnation who was born in Urgeling—a monastery administered by Tawang Monastery and a place that I would eventually visit—as well as the current Dalai Lama who took refuge in Tawang while escaping the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1959.

I hiked through narrow and steep footpaths commonly found in such hilly town to reach the monastery. While I rested on a short wall, a really old lama who did not know much Hindi or English offered me some savoury sticks. He even asked me to pass on a couple of them to a young lady who was clicking a selfie against the backdrop of Tawang town that’s visible from the monastery. The lama led me to the main building of the monastery and opened the doors to the prayer hall. I would later learn that that it is alright to open the gates or remove the cloth curtain and enter the prayer hall by oneself unless the door is locked.

A couple of young monks were playing cricket near the stairs of their living quarters. They did not want to have their pictures taken. Two of them were camera shy. I would eventually encounter this shyness of the monks and the local people multiple times during my trip.

On my way back, I stopped at Dharma Cafe for a cup of espresso and a slice of banana-walnut cake. They had a small collection of books for reading that were mostly related to Buddhism and Dalai Lama. The vibe and decor reminded me of some of the more hip coffee places in metros. I must say that I enjoyed their cake.

While returning, I also met Kumar at a garage near the Buddha Statue. He was repairing his Sumo for his Tezpur return trip the next day.

In the evening—well ahead of the 7:00 pm closing time—I bought some momos and fried rice for myself and some deep-fried fritters for sharing with the young manager of Hotel Samdrupling—the 19 years old Akash—and his even younger helps—the 10 and 12 years old Amit and Lobsang respectively—while listening to their stories. But more on them later.