MW was published in Big Comic from 1976 to 1978. This was a few years after Tezuka’s own comics magazine, COM, folded in 1972. Serialisation began right after the end of Vietnam War in 1975. MW—the titular chemical—is a fictional counterpart of dioxin. Dioxin or Agent Orange was used by the US to launch a chemical warfare in Vietnam. It is no coincidence that both MW in the manga and dioxin in reality were stored by the US military in an Okinawan island. Tezuka’s displeasure over the war and the use of Japan as a base by US troops is clearly evident.

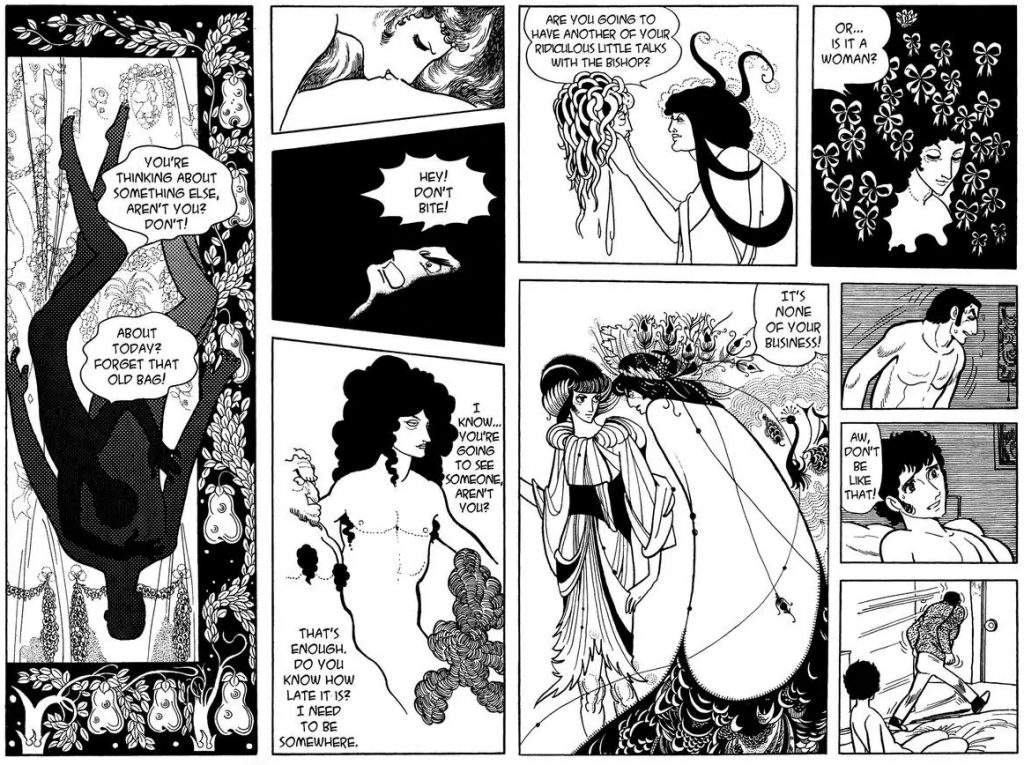

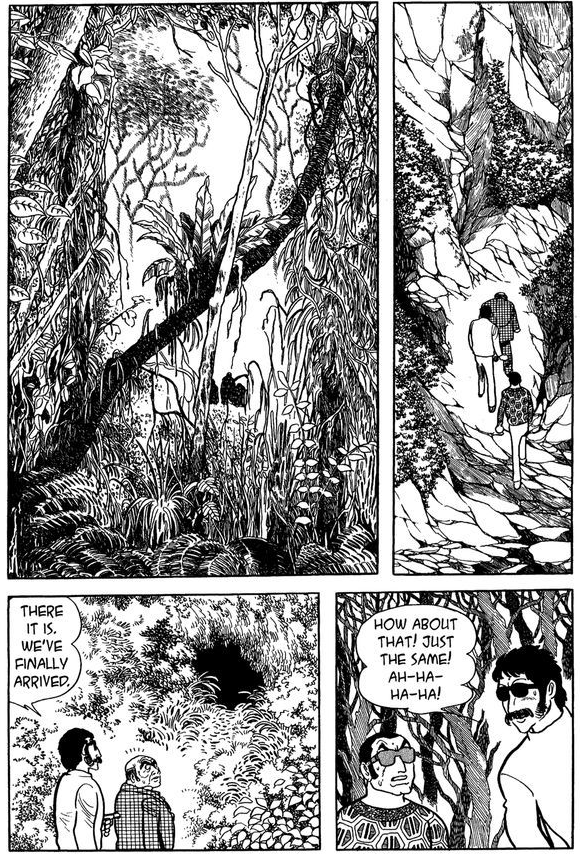

MW is a dark tale. It is possibly the darkest manga penned by Osamu Tezuka. The central character—an antihero called Michio Yuki—is a cunning, lustful, and a cross-dressing serial killer. When he was a kid, he was exposed to a lethal gas called MW that altered his sense of morality. The gas itself had wiped out an entire village. He and the deuteragonist are the only two surviving human beings who have witnessed the accidental massacre. The Japanese government have suppressed any news of the incident and over the years have repopulated the island—thus erasing any traces of the incident.

Yuki’s ideology is hard to pinpoint. On one hand he wants to destroy the politician who was responsible for covering up the incident and on the other hand he wants to get hold of the gas itself, which by now is no more on the island.

As the tale progresses, Yuki kills and damages the lives of many individuals, including children. Many innocent people are victims of collateral damage. Since the character lacks a clear motivation, he thrives on anarchy. He is the devil incarnate.

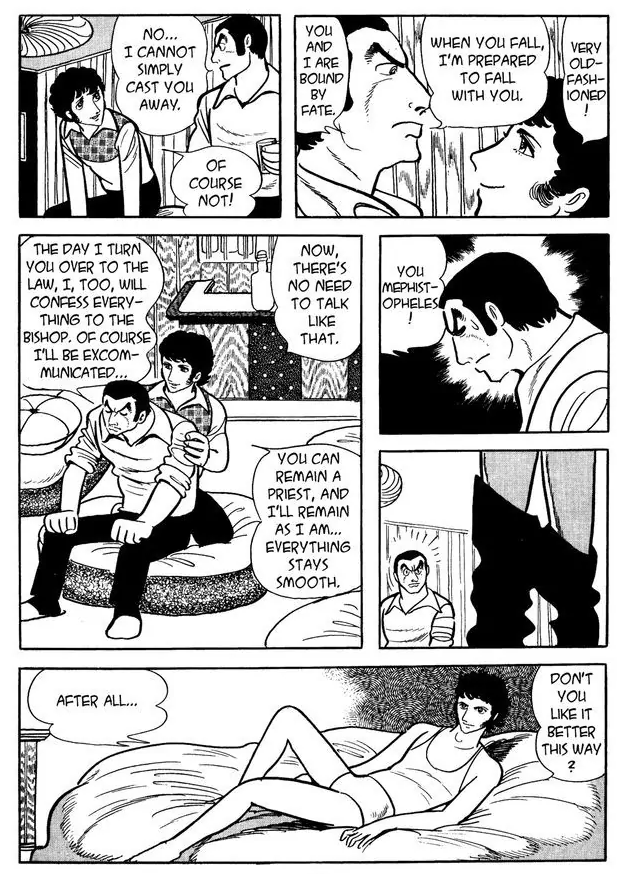

The deuteragonist of this tale is a priest—Father Garai. He was the one responsible for saving Yuki on that fateful day. He is torn between his sexual love for Yuki and his duty as a catholic priest. It is implied that Yuki has some sense of attachment to Garai as he doesn’t try to harm him. They share a strange dynamic. Garai doesn’t want Yuki to get into danger or even face consequences of his actions, yet his moral code compels him to at least attempt at saving Yuki’s victims. I say ‘attempt’ as he is unable to save anyone—and this includes the metaphorical salvation of Yuki himself. This makes him a far more interesting character in the story.

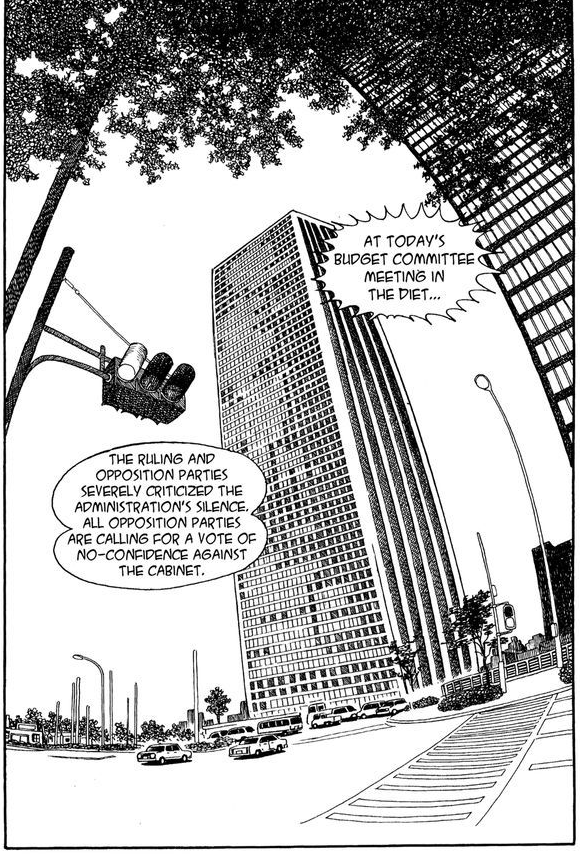

The manga follows all the classic tropes of film noir—the downward spiral of Garai, Yuki as a femme fatale, and a calculative detective who tries to connect the seemingly unrelated kidnappings and murders. The story itself is a series of misfortunes. Each and every misfortune propels the story forward and our characters further into the rabbit hole. The denouncement is also very anti-climactic. There is an ambiguity in the outcome (not giving out any spoilers here). The final panel is just a cityscape—as if our characters are lost in the city somewhere and we are now metaphorically out of the scope of the tale itself.

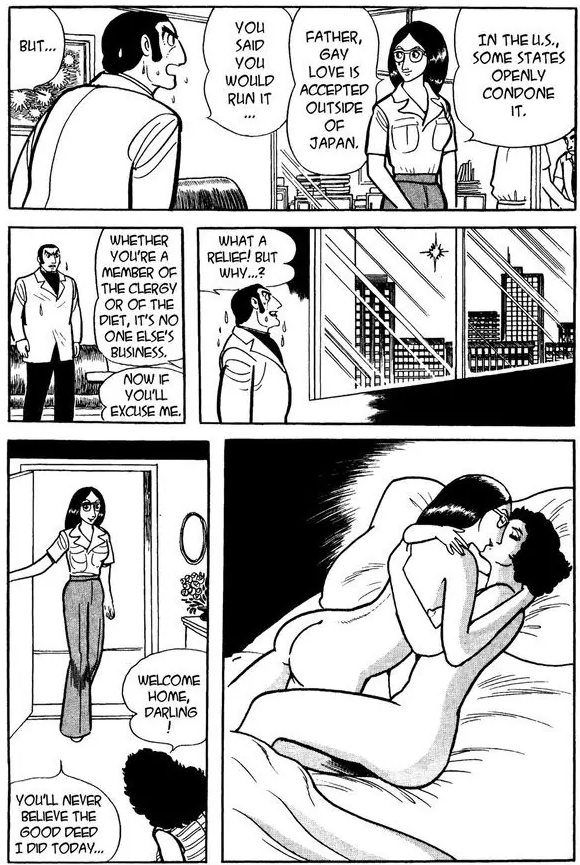

Tezuka is not afraid to take a stance on homosexuality. I imagine that drawing panels depicting homosexual intimacy would have been a bold stance in the late seventies. In fact, it is one of the important threads of the story and the source of Father Garai’s conflict. Tezuka’s support for legalising homosexuality is evident from a few panels devoted to the conversation between Father Garai and the editor of a magazine where the latter refused to publish an unsolicited image of Garai taken by a photographer and jeopardise his social status. The editor herself is shown to be a lesbian living with her partner.

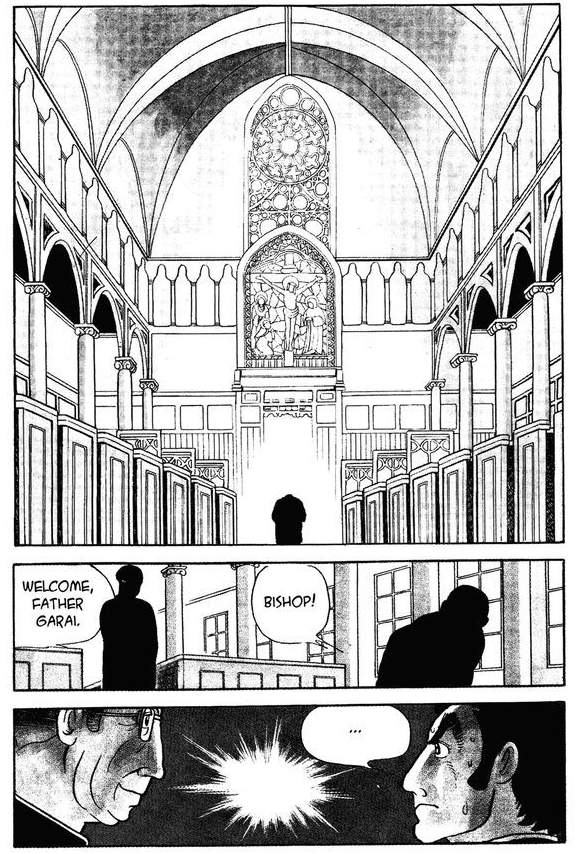

The art is unmistakably Tezuka. Technically, the manga is part of the gekiga (dramatic or cinematic pictures) movement. The art-style is much more realistic than Tezuka’s earlier shonen works. Being a thriller—steeped in film noir vocabulary—the manga lacks the usual gag panels, slapstick humour, and breaking of the fourth wall that are found in some other seinen or adult titles penned by Tezuka. Vertical has obtained the art from good sources. For a manga that was published in 1976, the lines are crisp and sharp. As such, all panels that showcase Tezuka’s detailing, stand out.

The gekiga genre’s cinematic influence is also evident in many panels where the vantage point and framing of a scene is directly borrowed from the movies. These techniques have become ubiquitous in today’s comics. It wasn’t so in comics from this era. As such, this manga could be one of those earlier works where these techniques were slowing becoming part of the comics vocabulary.

There are a few panels—especially near the end—that depict aeroplanes. These are excellently drawn and reminded me of Hergé’s attention to detail when it came to drawing transportation vehicles.

MW is a good introductory work for someone who wants to get into manga. Vertical’s edition—the one I own and the one that is widely available—was first published when manga was not that popular in the English-speaking countries. Like many of the early translated works, this one has its pages mirrored and thus, reads from left to right.