Blue Is the Warmest Color is the first full length graphic novel by Julie Maroh. It was originally published in French as Le bleu est une couleur chaude.

A character composed of letters and diary entries

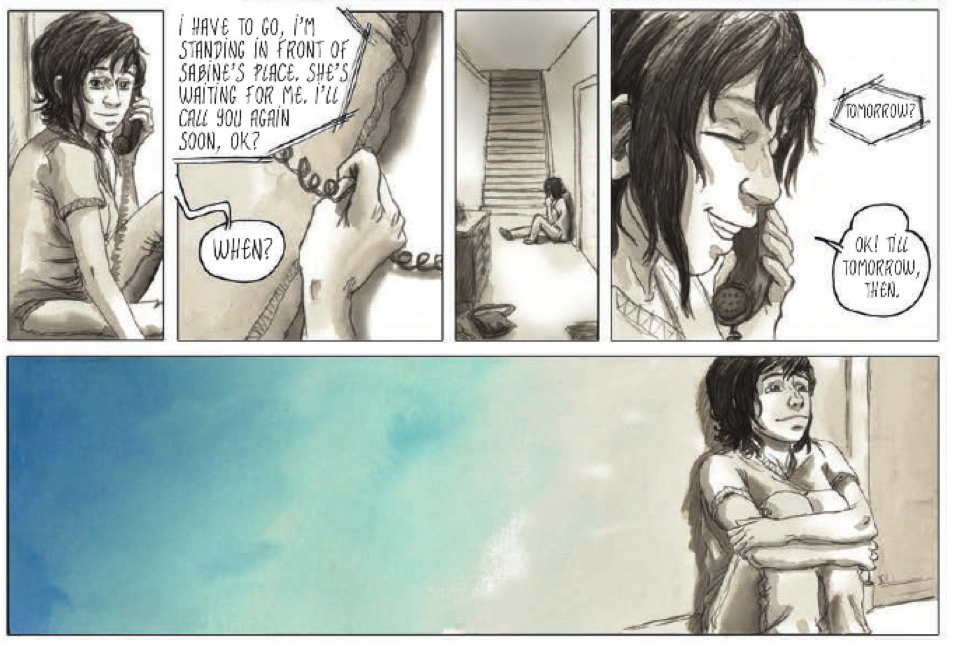

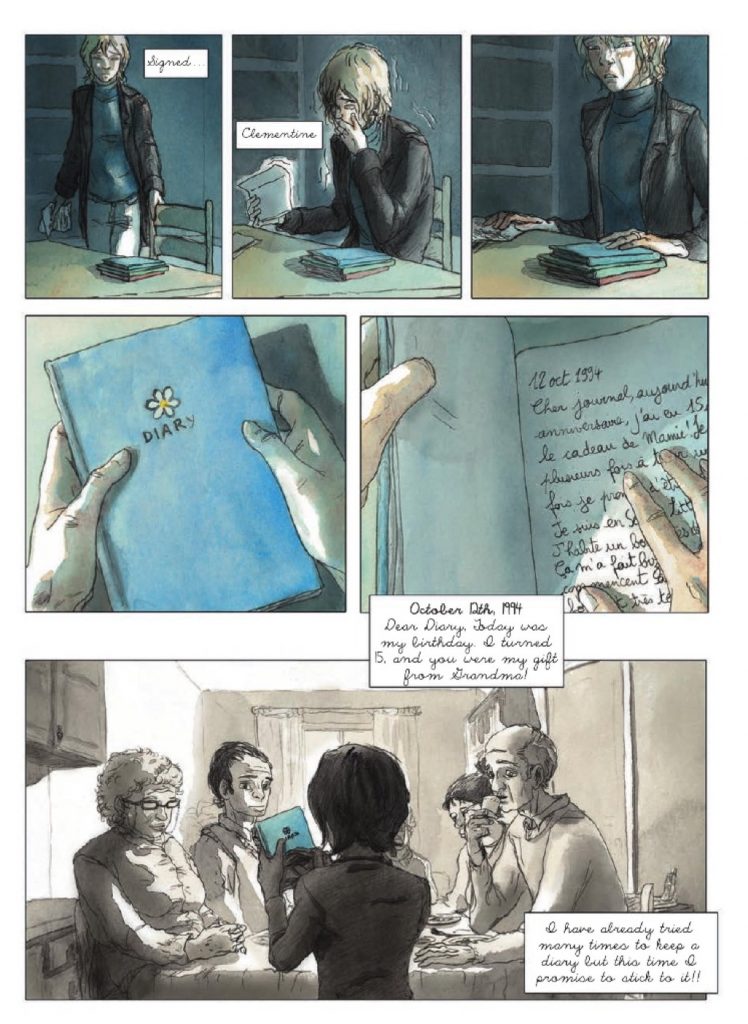

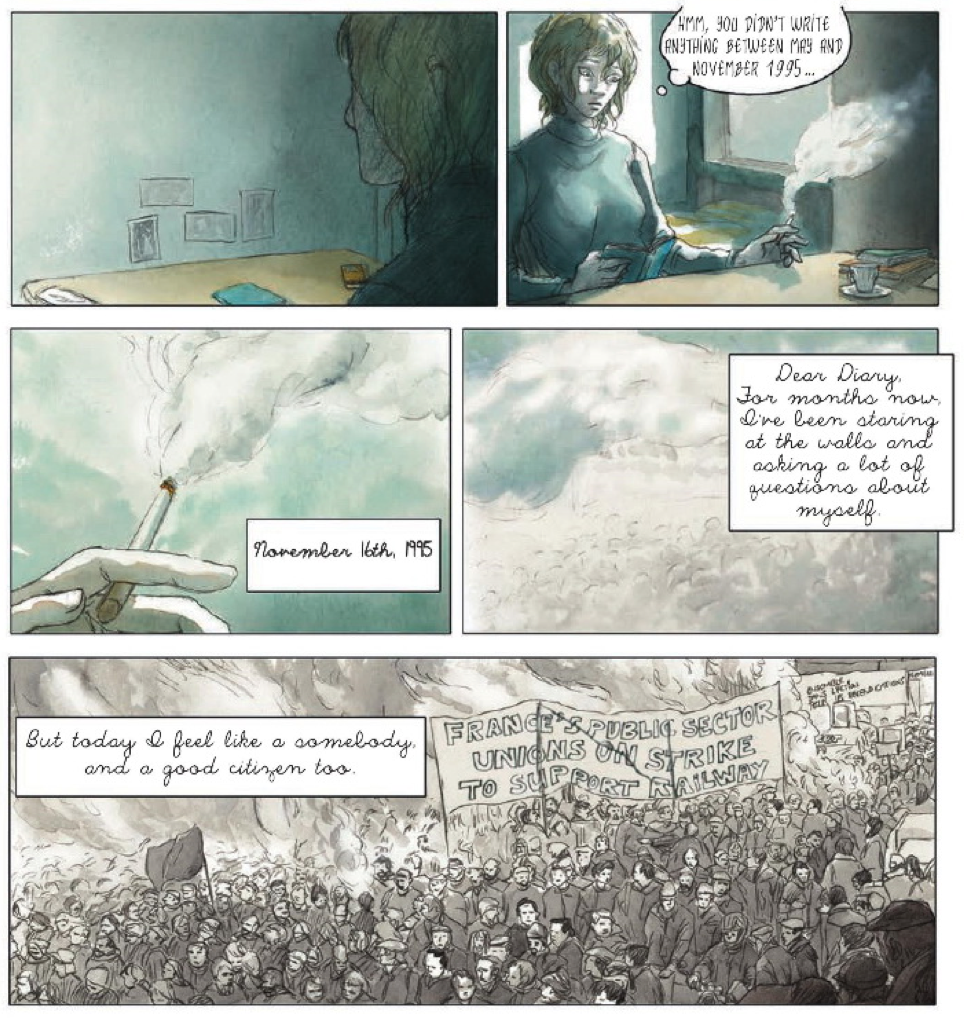

Julie Maroh constructs the story from letters and diaries left by the protagonist—Clementine—after her death. The recipient is Emma—Clementine’s long time partner. For most parts, Emma has been part of the events that are depicted in the story. Through the epistolary device, we are exposed to Clementine’s side of story—her thoughts, her feelings and the aftermath of various events—and thus to her character.

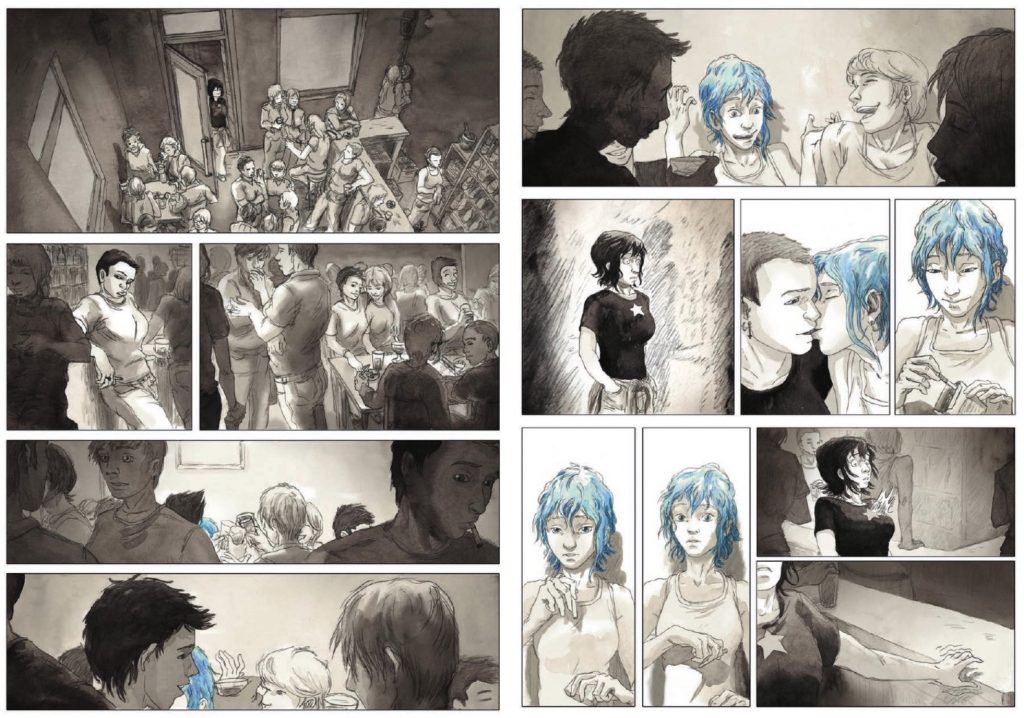

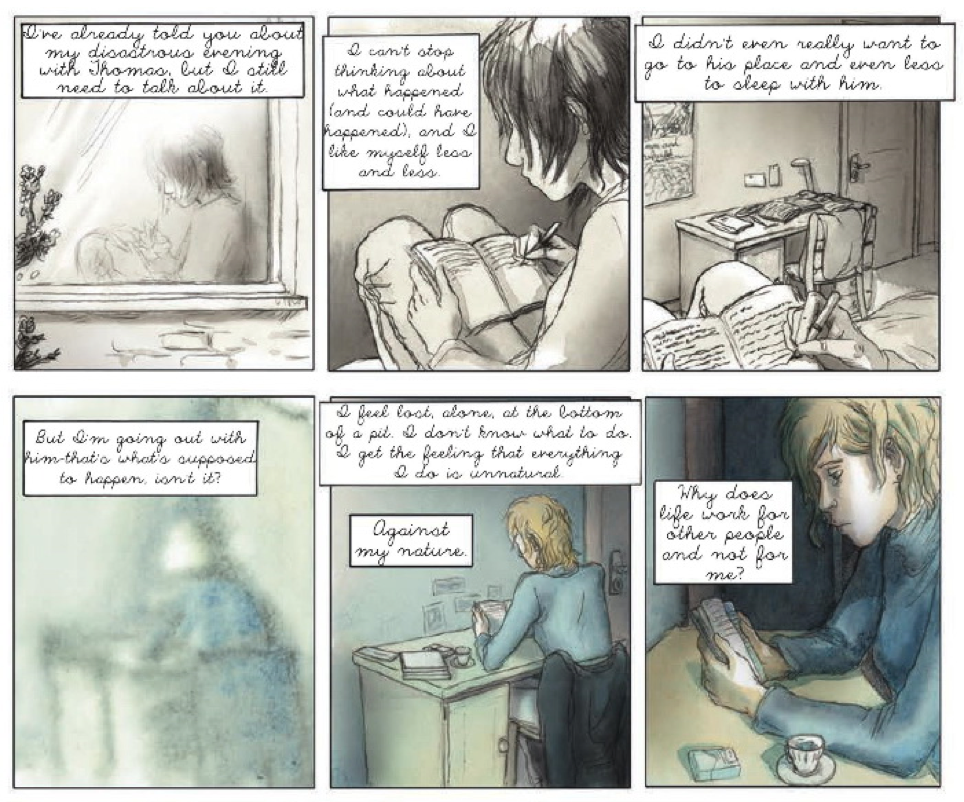

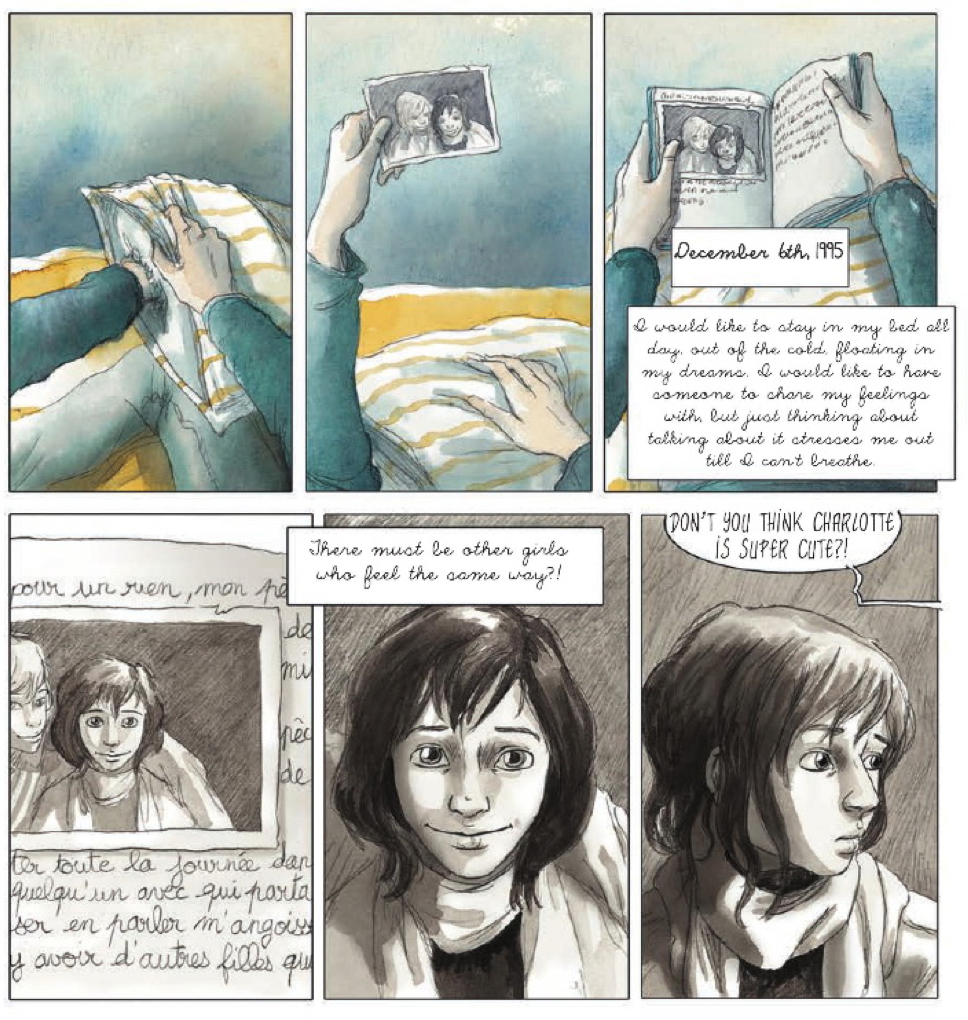

Story-wise, it is very poignant. There is an underlying drift of melancholy. Julie Maroh strictly focuses on Clementine’s teenage years—the tumultuous and exciting journey of self-discovery, of her sexual awakening. The narrative also touches upon themes of doubt and social acceptance amidst the optimism of young lovers. Julie Maroh devotes four pages to a lesbian sex-scene right in the middle of the book. It flows well with the narrative.

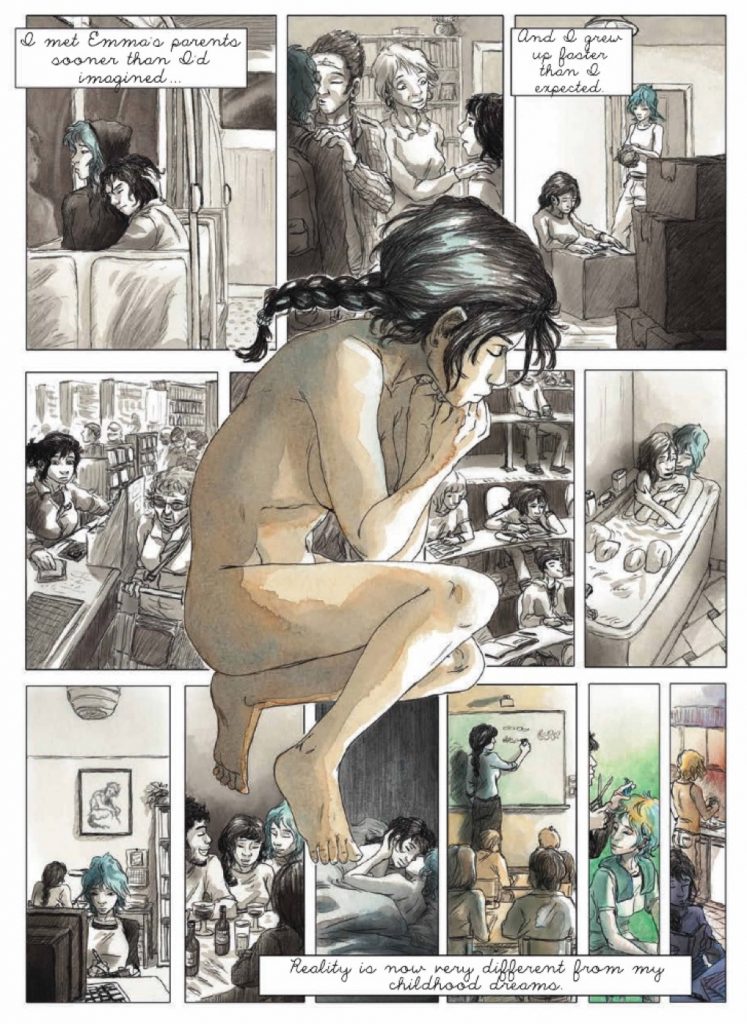

The narrative ends when Clementine is ousted from her house at the age of seventeen—when her parents find out that she is a lesbian. The page following that is a montage of events that fast-forwards the timeline by thirteen years.

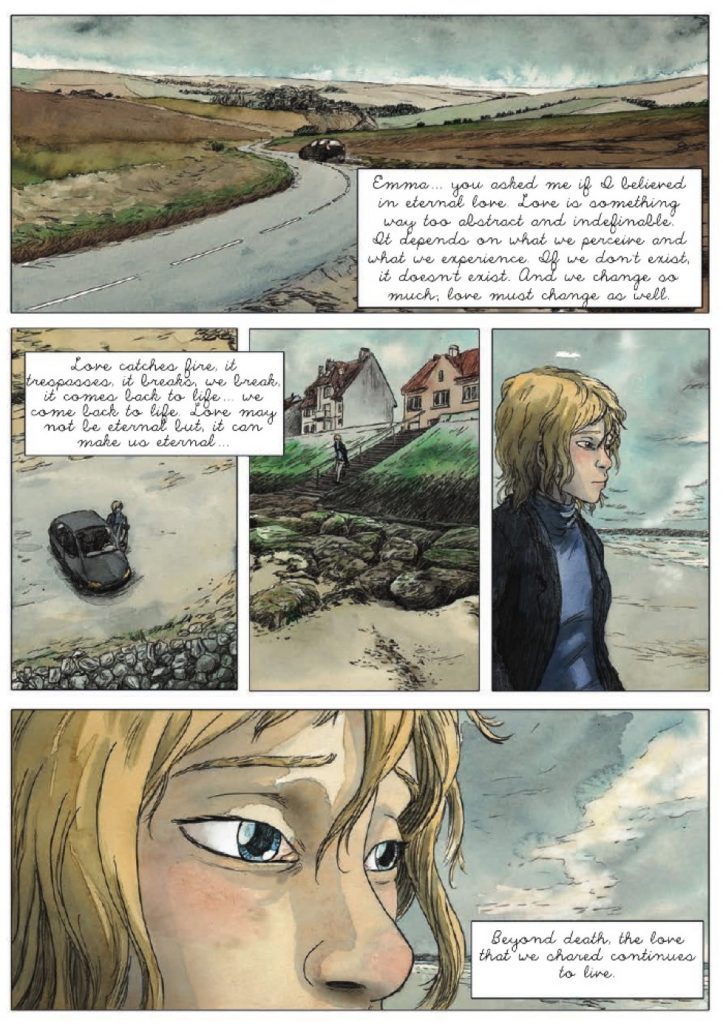

The ulterior point of the story is to acknowledge the variations in the idea of what love and sexuality could mean. Even though Clementine is the main protagonist, and her final letter clearly mentions what it meant for her, and how Emma had contributed to the meaning, the other characters also have different notion of what it means. We—as readers—observe the manifestation of this difference with Thomas—the first guy whom Clementine dates, with Valentin—who is happy to pick up guys at bars—as well as with Emma. This is mentioned in one of the panels where Clementine observes, “For Emma, her sexuality is something that draws her to others, a social and political thing.”

Blue is a character

The artwork gives away the fact that the graphic novel is a Bande Dessinée. Julie Maroh’s art style uses a modern vocabulary that is a stark departure from ligne claire (clear lines) that thrived in the mid-twentieth century. Her lines are jagged and sketchy. Yet, the shapes of objects aren’t distorted. She draws the eyes of her characters very well. They are very expressive—almost like a slightly toned-down aesthetics of manga.

The artwork is mostly done with ink and water colour. The timelines of the narrative have distinct colour palette. The present is colourful but feels very soggy. The colours are applied with a lot of wash. This goes well with the theme of melancholy. The past is depicted in black and white. Except for certain objects that have a nice wash of ultramarine blue over the otherwise near-grayscale images. These objects pop out of the panels for the reader. These are the things that the protagonist—Clementine—is attracted to. These are the things that stand out in her memories.

The transitions between the scenes—and there are quite a handful of them in the beginning—are also well made.

Amidst the snapshot of events that take place, once the past narrative is over, Julie Maroh re-introduces colours in the final three panels of the montage. This time it is yellowish orange—a colour that is diametrically opposite to blue. Interestingly, Emma gets rid of the last strands of her dyed-blue hair. This is almost like a symbolic severance of Clementine’s amplified teenage emotions.

As the entire palette of colours gets introduced into the panels, the cold, soggy, and melancholic feeling of the present creeps back in. It wraps up the narrative—we have reached the bleak opening.

My thoughts on the graphic novel

Julie Maroh—in an interview—had categorically pointed out that even though she is a lesbian, the story isn’t autobiographical. In fact, we could take the sexual orientation aspect out of the story and the story would still function. This is best described by Emma herself when she says to Clementine’s mother, “Just tell him [Clementine’s father] that if I had been a guy, Clem would have fallen in love with me anyway.”

There is one thing that I didn’t like in the book. The introduction of a heart condition and the pills Clementine took near the end of the book. It felt like a deus ex machina. Any hint in the earlier parts of the narrative would have mitigated that weirdness. In the story, it is the sudden excitement of seeing Emma once more and getting close to her delivers the fatal blow to Clementine’s heart and leads to the denouncement.

By the way, I haven’t seen the film La Vie d’Adèle which is mostly based on this graphic novel. The cover of my paperback copy says that it won Palme d’Or at Cannes. It must have. Film or not, this work definitely stands on its own.