Nowadays I enjoy some bit of hiking and backpacking. It wasn’t like this. Allow me tell a story that started it all. It is also a story that involves failures of spectacular proportions. I hope that would be mildly entertaining.

In April 2008, I was about to complete my second semester as a doctoral candidate. I had made some new friends—a few with whom I shared the same residential wing in my hostel and a few who were fellow research students in my department. Someone floated the idea that we should go for a trekking trip that summer. A spontaneous, and slightly risky idea thrown to a group of enthusiastic, young bloods is like a bone tossed amongst a pack of hungry dogs. I don’t remember who suggested it in the first place, but five people were definitely enthused by the idea of breaking the monotony of sedentary research work with some physically involving adventurous travel.

Besides me, it was Partho—a friend from my department, Prabir and Bhanu—my wing-mates, and Vivek—a friend from a different residential block—who volunteered to be a part of this audacious plan.

Chapter 1: How to build a fortress in the sky

Our naivety knew no bounds. We went through whatever trekking plans were available online for Sikkim and Darjeeling. This was 2008. People did not put out so much information on the internet. After scrolling through a list of all possible trekking routes, we chose one of the toughest treks we could lay our hands on—the Dzongri–Goecha-La trek.

One of the problems that a research fellow faces is the number of consecutive leaves that they can avail. Having zero experience, we deduced that seven days would be enough to do the trek. Vivek even suggested that we could easily cover the first twenty-six kilometres on the first day. In order to gauge the levels of our incompetence, I urge you to check any trek operators website in 2019. The minimum number of trekking days would be nine with most operators quoting eleven to twelve days for the entire trip.

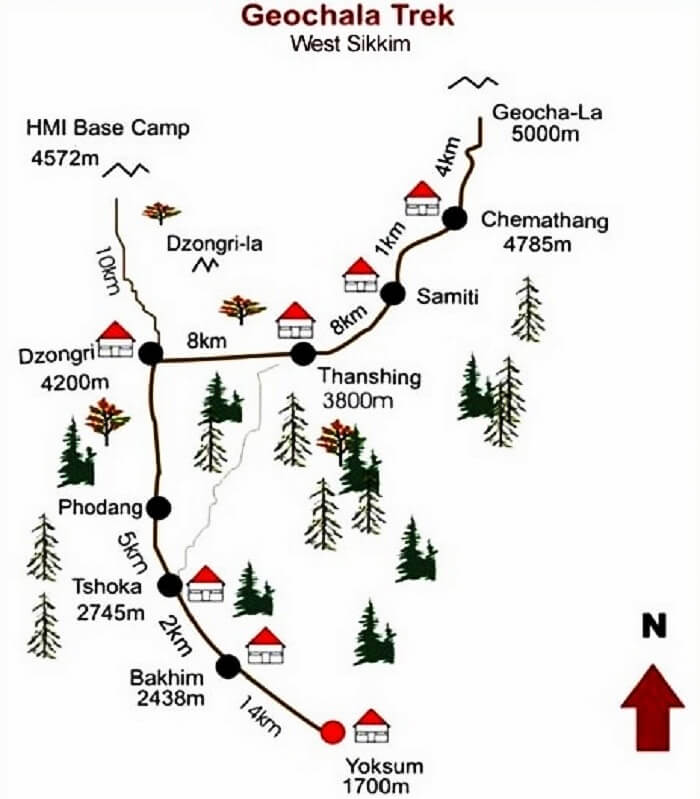

It might be worthwhile to have a look at the following image in order to memorise the names of the places. You’d only have to concentrate on the single line stretching from Yuksom to Dzongri. This is the exact map that we had as reference when we were planning the trip.

Once our atrocious plans were finalised, we booked our tickets from Sealdah (Kolkata) to New Jalpaiguri—the town that acts as a gateway to the Sikkim and Darjeeling Himalayas—and back. Our onward and return journeys were spaced apart by nine days.

We did not have any gear. Prabir contacted Alpine—an equipment company in Kolkata—and got most of the rentals sorted. (They are still in business!) We rented our rucksacks, sleeping bags and a couple of down jackets from them. Vivek and I bought some canvas daypacks from a local market. Partho already had a pair of Hi-Tec hiking shoes, Bhanu had his dad’s military boots that he wanted to re-purpose, Prabir and Vivek wanted to use whatever sports shoes they already had. I did not own anything other than a pair of formals. So, I bought a pair of Woodland shoes. I thought that those heavy boots would be really great for trekking! (How naive!) Meanwhile, Partho had sourced some of his father’s contacts to arrange a part of the transportation as well as accommodation in Yuksom—a settlement that marks the end of motorable road and the start-point of the trek.

We were all excited. We packed all our stuff. We had it all set to pick up our rentals and reach in time for the evening Kanchankanya Express at Sealdah. That’s when we got our first bad news. Remember the getting-a-leave issue? This turned out to bite back at Vivek. He dropped off right at the last minute unable to get his leave sanctioned by his supervisor, thus leaving us with five tickets and four passengers. Later that afternoon, while picking up our rental gear, the owner of Alpine asked where we were headed. On hearing that we were about to go to Goecha-La, he gave us a strange look and thoroughly scanned our not-so-fit bodies. He asked with a worried tone if we had trekked before. When we said no, he shrugged his head and gave us the rental gear.

Some of our relatives who stayed in and around Kolkata came to see us off at Sealdah station. The train was already on its way when a poor-looking old man came and sat with us. He did not have a confirmed reservation and was looking for a place to sleep. Since we had an extra reserved berth, we asked him to take that place. That old man would forever be known to us as Proxy Vivek.

Chapter 2: We’ll prep it on the go

I remember bidding farewell to Proxy Vivek the next day on New Jalpaiguri platform. We were headed towards Jorethang—a town near the border of West Bengal and Sikkim. We had to catch a shared cab for that. We bought a stove from New Jalpaiguri market so that we could cook our meals during the trek. Also, it sounded like a good idea to carry it back to our hostel rooms once the trek was done. We got the cheapest kerosene wick stove that we could find. I don’t remember who paid for it but I remember Prabir carrying it in a plastic bag for the entirety of our journey till Yuksom.

My memory fails me but I think it was somewhere near Jorethang where we met up with a friend of Partho’s father. He informed us that had arranged the government guest house in Yuksom but it would only be available once we would have returned from the trek. The other thing that I can recall is me having Thukpa (or Gyathuk as the Sikimmese say) for lunch and enjoying it thoroughly.

The next morning, we sat in one of the rented inns at Yuksom and negotiated our terms with a local trek leader-cum-porter, Mr. Bahadur. When he saw our itinerary, he laughed. We had charted a five-day trek to Goecha-La and back. He mentioned that we would only be able to go till Dzongri in five days. He also saw our wick stove and had a second laugh. At higher altitudes, the only reliable cooking apparatus are those that use wood or pressurised fuel. The kerosene stoves that are used are of the pressurised variety where the flame is fuelled by kerosene vapours. He agreed to buy it off from us. During the same time, Partho got a threatening call from his father. His father had done some research on his own and figured out that Goecha-La required a lot of preparation. There were even cases where someone had died or had gone missing. Panicked by our stupidly brave attempt, he called his son up and warned him that he would file a case with police if we attempted to trek in Goecha-La.

At the end of the day, we had a solid six-day plan to Dzongri and back. We would be ascending the twenty-six kilometre route in three days. After that, we would stay there for a day and descend in two days.

For most of our two-night-and-one-day stay in Yuksom, we had food at Yak restaurant. I don’t know if that place is still open. It is there that we met a young film-maker who was heavily inspired by Dogme 95 films and the tongba he drank—fermented millet in hot water served in a bamboo container. He kept pouring hot water in his bamboo tumbler containing fermented millets and explaining all the things that made Dogme 95 films great. It had already been three years that the movement had broken up; and eleven years later, it feels like an elitist genre. I believe his passion wore off the next morning along with the tongba.

Chapter 3: Choice expletives can alleviate exhaustion

On the day the trek began, Bahadur got his nephew to assist him. I don’t remember his name, so let’s call him Nephew. We were supposed to cover fourteen kilometres that day all the way to Bakhim. The terrain was not something we had experienced earlier. We were following Bahadur and his nephew through climbs and valleys, traversing one hill after another. Most of the valleys had suspension bridges over rivers. Looking down was scary.

We were also carrying a ton of weight. All of us had a rucksack on our back and a daypack hung in front. (See specimen below.) I had personally stuffed whatever I thought would be good for the temperatures in my bags along with chocolates and dry fruits—lots of them.

We did not have to go that far. Prabir and Partho were quite exhausted at Sachen—a place somewhere in between Yuksom and Bakhim. I remember that place having a solitary, uninhabited trekker’s hut. This place wasn’t mentioned on the map! We all rested inside while Bahadur and Nephew prepared food for us. They were not prepared for this stop but in retrospect I think they kind of expected it from us. The only thing I remember from that night is that I went out to defecate and the cold was punishing my bare bottoms.

Bahadur had sensed that we wouldn’t be able to do the trek without some motivation. The next day, he pushed and encouraged us. Just after Sachen was a two-kilometre-long steep descend into Prek valley and another two kilometres of equally steep ascend. The gradient at places was close to 100%. (I can not vouch for the accuracy of that data but it definitely felt like so.) That stretch had tired Prabir and Partho even more. So much so that they did not want to hike all the way to Bakhim. Instead they took a weird shortcut that had clear warning signs posted near the onset. Bhanu and I took the usual route.

We reached Bakhim much earlier than Partho or Prabir, who were lost somewhere in the woods. About half an hour to an hour later, we heard loud expletives. Their exhaustion manifested in a few curses directed at the terrain—and possibly themselves—as they emerged out of the woods. Partho threw a filled one-litre PET bottle into the valley below as a drastic measure to reduce weight. Meanwhile, Bhanu tried to coach them with some yoga-inspired breathing techniques. He claimed that it would ease their exhaustion. Needless to say, some of those expletives ricocheted off the valley to hit Bhanu.

We would have stopped there had Bahadur not coerced us into proceeding to Tshoka. The large portions of Maggi that he prepared as lunch also helped.

Chapter 4: Koto koshto, poisa noshto

We reached Tshoka that day. That sentence was easy to write. The event is also easier to recall than the actual event itself. We had rented a four-person tent from Alpine and wanted to use it at least for a night. Bahadur and Nephew got down to set up our tents and prepare our dinner at the Tshoka campsite.

We ventured out to a nearby grocery-cum-tea stall for some tea. When we asked for a large serving of tea, we were given some kind of orange liquid in a tall glass. It smelled like tea, it tasted like tea. Yet, I couldn’t figure out what ingredient would have caused its deep-orange colour.

“Is this Yak’s milk?” I asked the lady.

She nodded her head in affirmation, turned around, giggled and went back to her counter. The tea was godsend. After a few rounds of large servings, when I went to pay, the lady giggled once more and shattered our placebo of feeling energised by tea made with the milk of some strong, meadow-grazing, mountain-traversing yak.

“Not yak, shabji; Amul Gold, Amul Gold,” she said as she took the money and went back to making more orange-coloured tea.

Another young chap—the trek leader of a different (and more affluent) team—was done with setting up their dinner tent. He had seen and heard our ordeals. He did not know much Bengali but knew enough to taunt us with a nice couplet—koto koshto, poisa noshto. The closest couplet in English would be, man exhausted, money wasted. We had no other options but repeat his couplet with a smile that reeked of extreme self-pity. For the next few days we would occasionally cross paths and each time he would repeat the couplet.

I also remember that Bahadur had prepared some rice, a potato-tomato curry and some dal for all of us. We were so hungry that we finished whatever was cooked leaving nothing for Bahadur and Nephew. Both Bahadur and Nephew ate thrice of our normal servings on a regular day. This would put into perspective the relative jump in the amount of food each of us consumed that night.

“Shabji, aap log bahut achha khaya (you guys ate well),” Bahadur said.

The next morning, an elderly woman from the other group had to be taken back to Yuksom on a donkey. She showed early signs of AMS. That same morning few of us also experienced how it feels to poop into a deep valley while holding on to a tree branch for one’s dear life. Yet, nothing could diminish our enthusiasm. It was that—and a lot of encouragement from Bahadur—which helped us reach Dzongri that day.

That night we played twenty-nine with a character called Gyabu sherpa. He and another thin person with him had done quite a number of expeditions and were preparing for an upcoming expedition. They were headed towards Goecha-La. He was pretty good at cards and had this tendency to slam his card while shouting “Veg momo!” I was fascinated with the headlamp he was wearing while he was more interested to know if we had some alcohol with us.

Bahadur woke us up at 3:30 am the next morning. It was still dark outside. We used handheld torches to find any signs of a walkable path. We were headed towards Dzongri-La—an isolated hilltop near Dzongri—to view sunrise on Kanchendzonga. I don’t remember much from the climb except that for the last few kilometres we had to walk along a sharp ridge. The sky wasn’t that clear either. My memories of that sunrise are all smudged by that dull, overcast sky. Still, it was the the highest point we had trekked to.

That same day we started descending. It took us two days to get back. Descending slowly in the mountains is like doing one-legged squats. Whenever one of my legs was fatigued, I switched to the other leg for leading my gait. Once both got fatigued, Bahadur cut a branch for me so that I could use it as a trekking pole. At times it drizzled. In the absence of a raincoat, I resorted to a plastic carry-bag worn like a cap over my head. Bhanu’s dad’s shoes were biting him hard. He was bleeding from his ankle. I made a makeshift cushion around the edges of his shoe with some medical tape and cotton. Meanwhile, the soles of Prabir’s sports-shoe had started to come off. Some amount of Dendrite (a resin-based adhesive) kept them from completely falling off. I lost count of the number of times we stopped to give ourselves some rest.

Once we were back in Yuksom that evening, the government guest house was ready for us. The most important part of that previous sentence is that we were back in Yuksom. Partho’s father was elated to know that his son wasn’t lost in the woods, or snow. We dropped all our bags, settled the bills with Bahadur and went off to sleep.

Chapter 5: Don’t we have a train to catch?

The next afternoon I found myself awake on a sofa in the drawing room of the guest house. I got down, stood up and immediately fell on the floor! I could not stand. My legs were busted. Bhanu was the only one who was able to walk around with his somewhat taped ankles. Prabir and Partho were still asleep. I was hungry but did not feel like walking fifty meters to reach any of the restaurants.

“Don’t we have a train to catch?” I asked Bhanu.

There was no way we would be able to get on a cab, drive all the way to New Jalpaiguri by the evening, get on Darjeeling Mail and occupy the seats that we had reserved a few months ago. Those seats would now be filled up with Proxy Sauvik, Proxy Partho, Proxy Prabir, Proxy Bhanu, and not to forget Proxy Vivek. I went back to sleep.

That night we used branches as walking sticks to inch our way to the nearest place that served food. Me and Bhanu gulped about twenty rotis that night. That demonic hunger would continue to shadow us for quite sometime even after we were back in our campus.

We managed to get on a cab in Yuksom and made our way back to New Jalpaiguri railway station. To expect any reservation at such a short notice would be a distant pipe-dream. Instead, we got three general compartment tickets (Bhanu went to his hometown) and got on a special train headed for Sealdah. The cramped compartment—where everyone jostles for their share of sleeping space and elbows when necessary—was a good opportunity to contemplate over the various life-choices we had made over the past few months.

Epilogue

Eleven years later, we have all drifted into our own worlds; earning, raising kids, contributing to society and being awesome in our own ways. Now that I look back, I laugh at our juvenile attempt at trekking. Still, it was an important moment for me. This instilled in me an appreciation for the mountains and made me realise that I loved mountains more than cities or beaches. It also taught me that preparation is as important as the trip.

Years later, I have replaced most of those make-shift equipments with reliable travel gear; raked up a ton of experience regarding travel; became a better observer and documenter; and to top it all, lost quite some weight and become fitter.

Someday I might revisit the trail. For sure, I wouldn’t be doing it in six days.

P.S.: Thanks to Bhanu for carefully archiving the images.