If there is one word that describes The Castafiore Emerald, it has to be deception. This is one Tintin album that is not like any of the other Tintin albums. There is no villain, no adventure, no travel, no action, or anything else that can be remotely associated with the hallmarks of a typical Tintin album.

This is a show about nothing. That being said, a show about nothing requires a lot of events and subplots to hold itself up—just ask Jerry Seinfeld and Larry Davis. I have no idea how Hergé came up with the idea of plotting an entire Tintin story inside and around a mansion. The opening deception is the emerald band that runs across the entire cover page announcing the album to contain one of “The Adventures of Tintin”. Tintin himself appears on the cover with his index finger on his lips, as if he is signalling the readers to keep the deception a secret.

The subplots of deception

There are too many subplots that construct this story. Here are the major ones that cover the sixty-two pages of chaos.

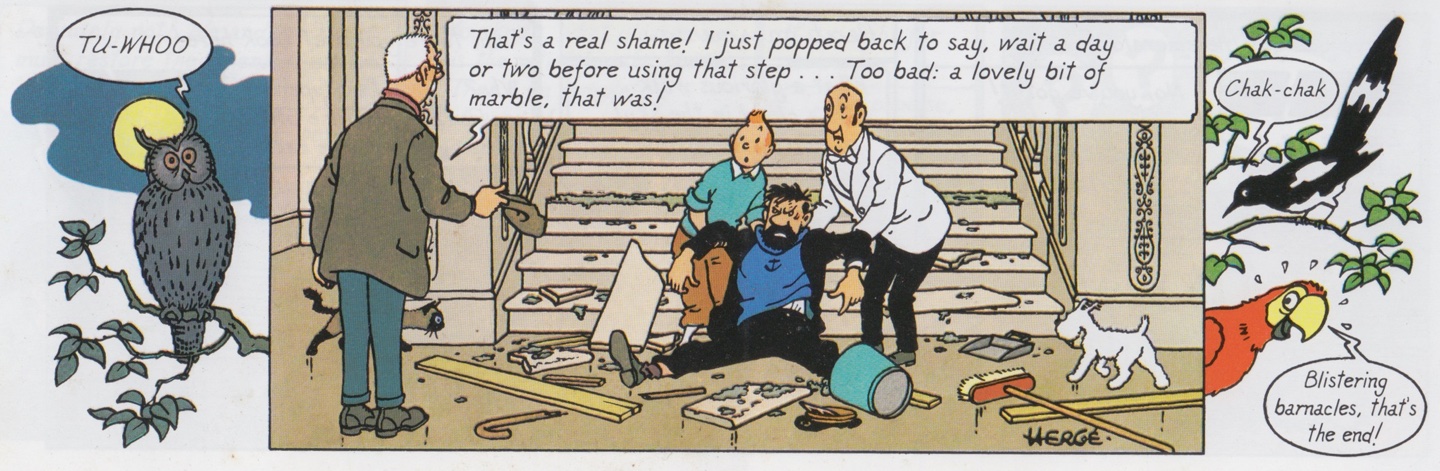

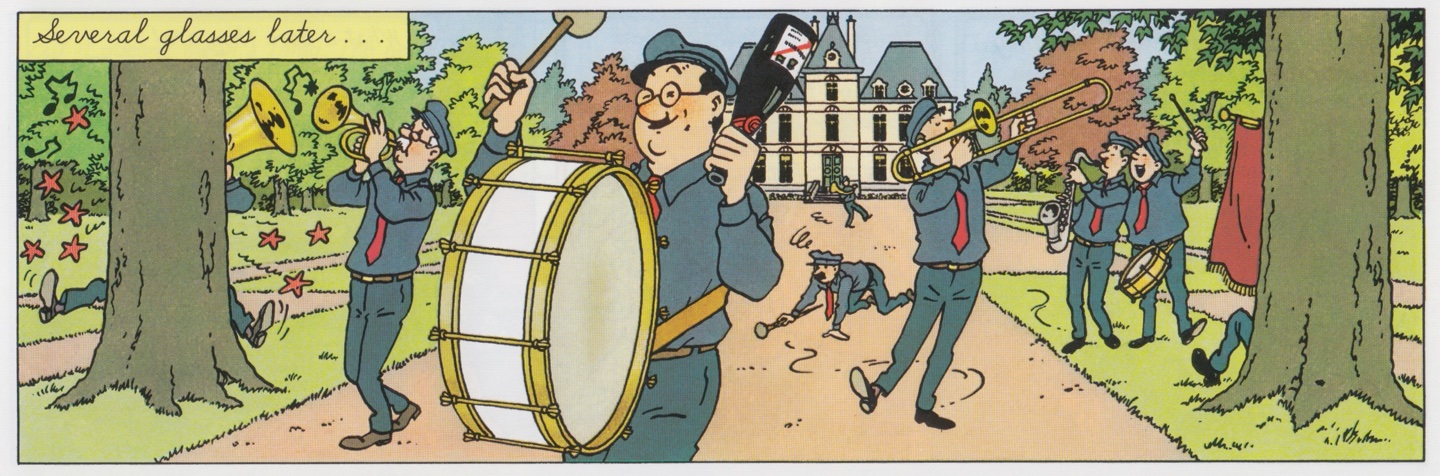

- Marlinspike Hall has a broken marble step on its staircase. This causes Captain Haddock to fall and injure his ankle ligaments right at the beginning of the story. For rest of the story, he is wheelchair bound, thus eliminating any chances of him venturing out for an adventure—or, for that matter, escape Bianca Castafiore. The root cause of this misfortune is the apathy of the contractor, Mr. Bolt, who does everything other than fixing the stairs. We even see him partying in front of Marlinspike Hall on page 30.

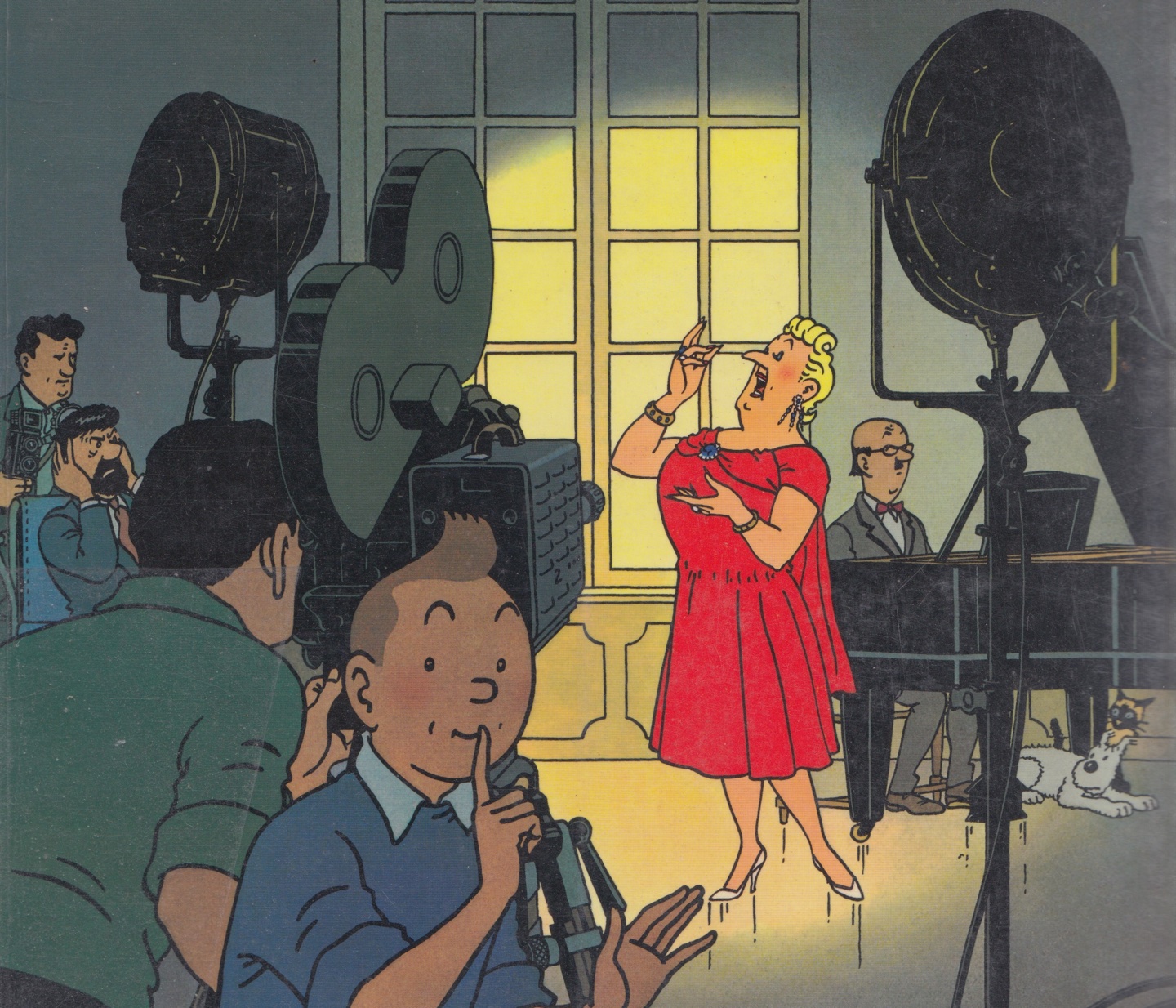

- Bianca Castafiore arrives with her maid and her pianist. Since she is a celebrity, the press and the TV crews follow. She is paranoid about losing her jewels. Even the mention of jewels triggers her paranoia. Her fears eventually come true. During a filming session, she is informed that one of her emeralds is lost. This forms the titular subplot that frames the narrative as a whodunnit. This event doesn’t even occur until page 43, which is 12 pages past the mid-point of the album.

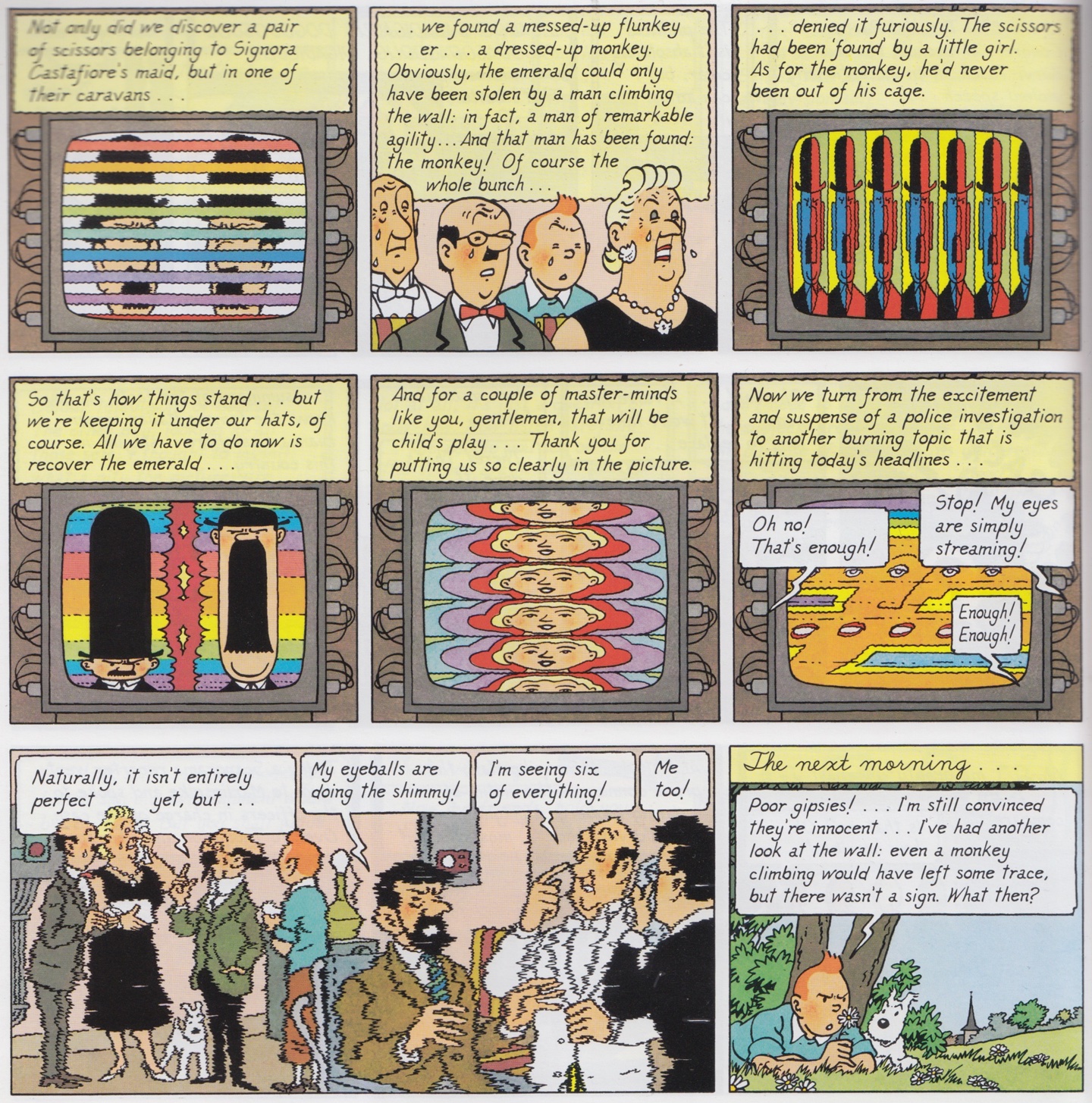

- Calculus has a crush on Castafiore and tries to impress her with his inventions—a hybrid rose and a colour television.

- Jolyon Wagg tries to sell Castafiore insurance for her jewels.

- A band of Gypsies setup their caravans near Marlinspike hall. They serve as the primary suspects for the whodunnit subplot. Like all good primary suspects in a whodunnit plot, they are merely distractions.

- Mr. Wagner serves as the second suspect. His unhappiness with Bianca Castafiore’s dominant personality and her strict orders for him to practice his piano at the cost of his gambling time motivates him to sneak out like a thief; thus unintentionally leaving multitude of clues in the environment that confuse Tintin as well as the readers.

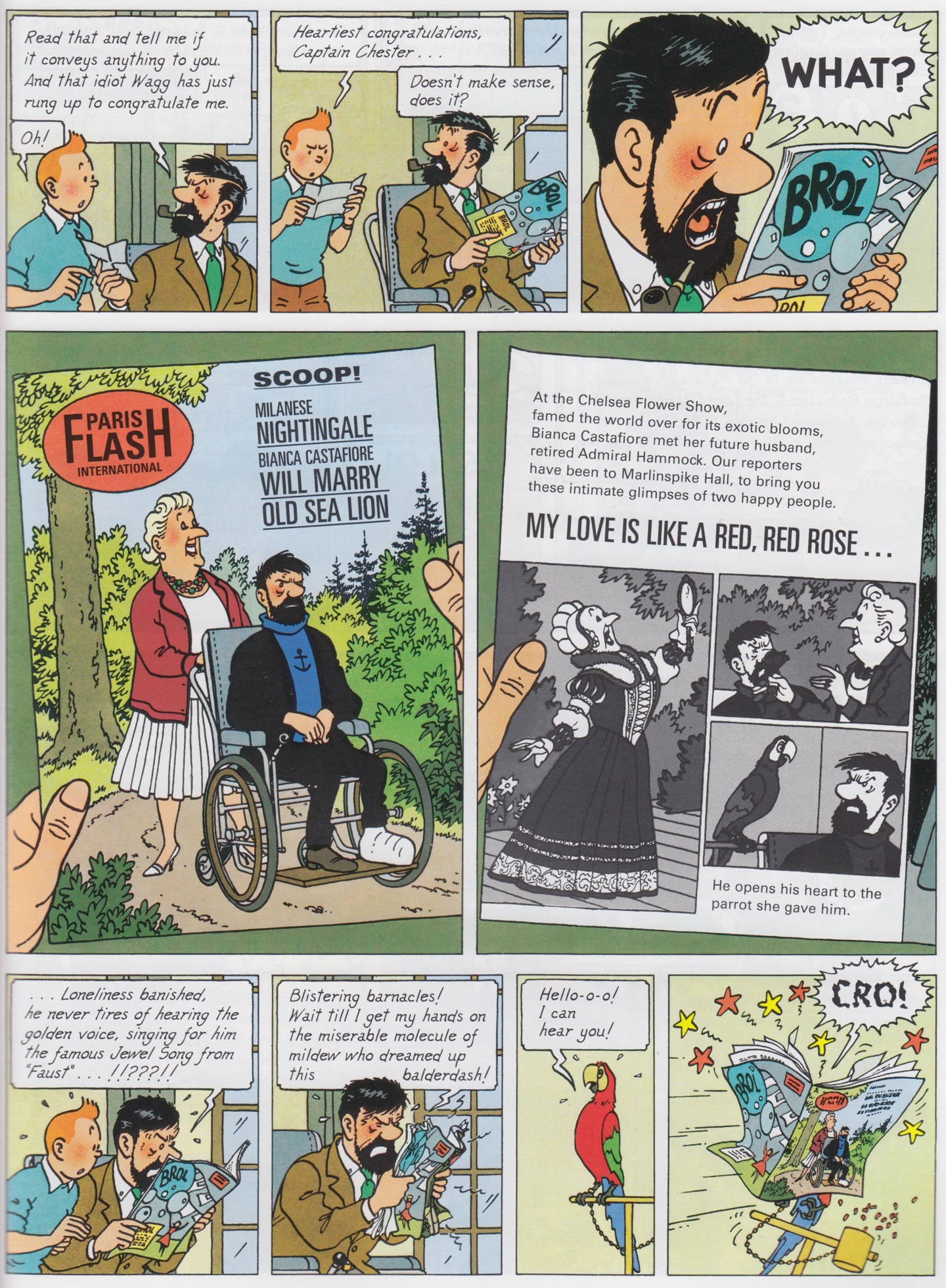

- Reporters of the magazine, Paris-Flash, visit Marlinspike Hall to interview Castafiore. Later, a television crew follows suit. Amidst all these, two paparazzi from a smaller publication, Tempo di Roma, sneak into Marlinspike to get a story. While Paris-Flash fabricates an entire romance between Castafiore and Captain, the singer is least bothered with it. She is more furious to have a feature in a nondescript magazine (and hates them because they had commented about her weight in an older article). It is also ironic that her sole purpose to stop at Marlinspike was to avoid the press. Instead, being the attention-seeker that she is, she allows the press and the television to interview her and give her some exposure.

- An owl roams around the attic of Marlinspike at night, giving the illusion of someone hiding there.

- Castafiore gifts Haddock a parrot, which itself is a nuisance for him. Yet, he isn’t able to let it go lest Castafiore be offended. To add insult to injury, the parrot parrots Captain’s slangs and his phrases of disappointment in front of unintended audiences.

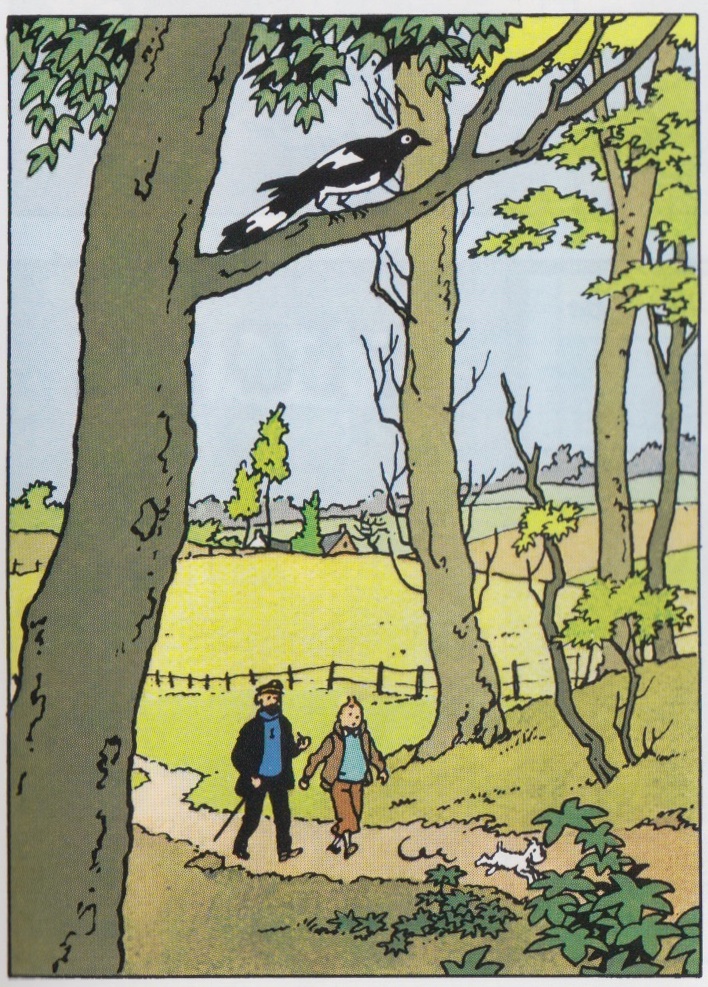

- Then there is the magpie that actually steals the emerald. The way Tintin cracks the mystery is also somewhat anti-climatic. He recalls that Castafiore had headed off to Milan to sing The Thieving Magpie which gives him a clue that a magpie might have stolen the jewels. Hergé foreshadows this by showing the Magpie on the very first panel of the album.

A tough follow-up

The previous album, Tintin in Tibet, came out in 1960. In my opinion (and many other Tintin fans that I know of), it is one of the best Tintin albums. It was hard for Hergé to top that. Sources point out that Hergé wanted to write another grand adventure and worked on two ideas before abandoning them completely. Instead, he opted for this whimsical, home-bound plot.

Tintin himself is an outsider—an observing, deducing detective, unfazed by the plots and subplots—a comic book Poirot. I do not know if the ending justifies the comparison but I wouldn’t be surprised if someone disagreed and said that Tintin acting like a detective was a theatrical deception in itself.

That being said, the maturity of Hergé’s artwork shows. In the absence of grand settings and action panels, he had a tougher job to sell his brand of satire. The reader can tell that he was more focussed on getting the expressions and the characters right.

I am not sure if kids would ever get this album. I read this in Bengali when I was ten years old. I didn’t understand what the story was all about. As a kid, I understood the plot but never appreciated the absence of a real adventure. I always followed this up with The Red Sea Sharks—a story more suited to my childish sensibilities. It wasn’t until I was in my late twenties, re-discovering Tintin, that I truly started to appreciate this album for what it is.

There are great panels in the album that captivated me even as a kid. One of them is the hilarious colour television demonstration by Calculus.

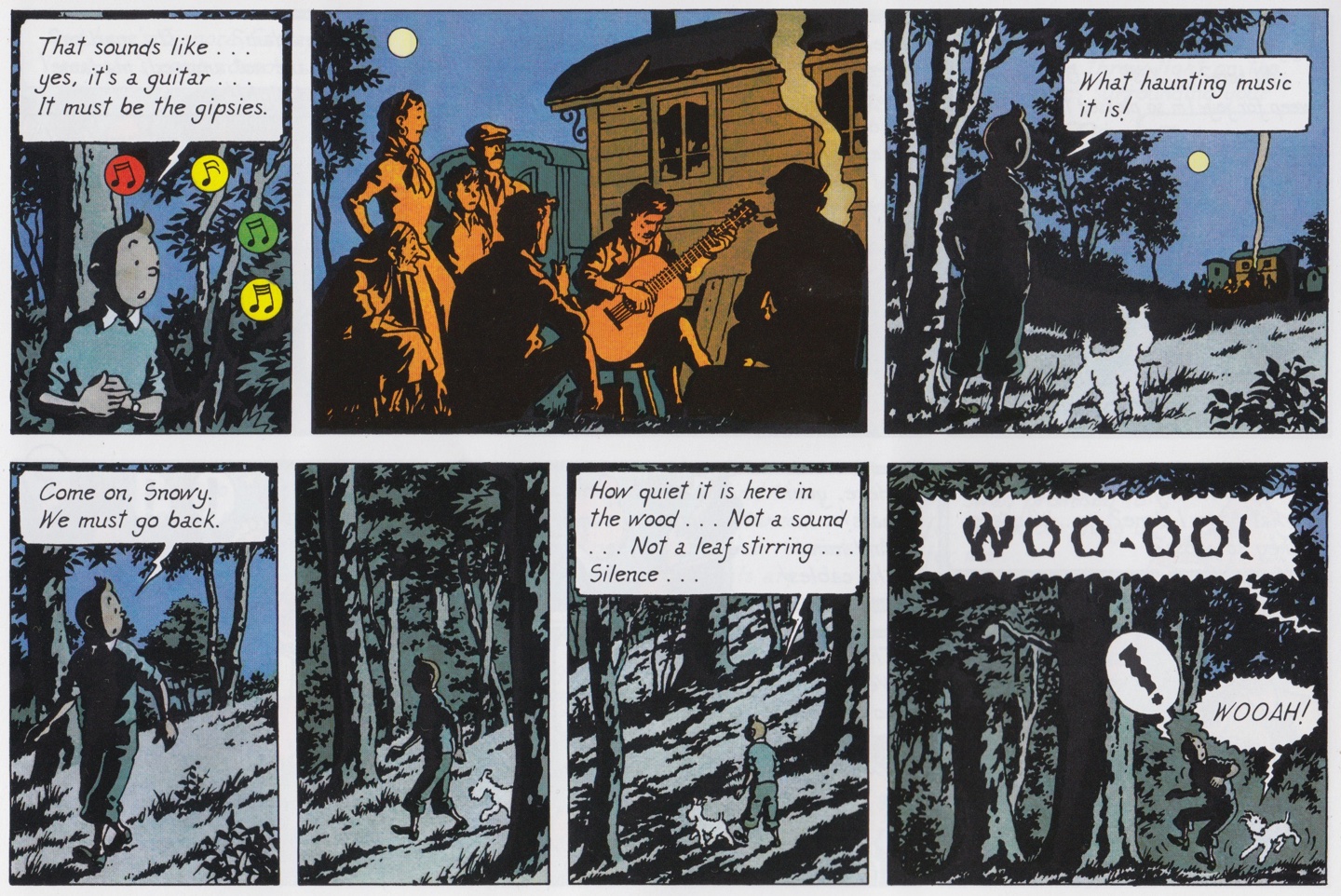

Then there are the brilliantly coloured night sequences. Sure, there are other Tintin albums that illustrate night-time events but none does so moodily as this album.

Enfin

The Castafiore Emerald is definitely an acquired taste. It is hard to recommend this as an entry to the world of Tintin. Still this outlier can be a great introduction to Hergé’s works for people who might eschew Tintin albums citing their lack of subtext when compared to more modern, formalist comic titles.

If you are a fan of satirical works, this is an excellent comic book. If you are an adult fan of Tintin but have always detested the weirdness of this book, I urge you to revisit this album with an open mind and some contextual background. If you are a teenager who has stumbled upon Tintin, please give yourself a few years to soak in some life experiences—you’ll appreciate this deceptive satire even more.