The Broken Ear is the first book with a preconceived plot. In the previous serialisations, Hergé had covered the four cardinal directions—Soviet in the North, Congo in the South, America in the West and China in the East. His approach to stories had changed much after his chance encounter with a fellow artist, Chang. He started using a notebook to jot down plot points, notes, sketches and references.

Breaking down a plot

Hergé had to still serialise the story, at a rate of two pages per week. He had to pack enough excitement and pace in those two pages while keeping some semblance of an overarching plot. He came up with a solution. The characters follow—or chase—the fetish until the mystery is solved. Each situation is still a compartmentalised event. Thus, dividing the story into smaller arcs, each with their own setup, environments, actions and gags. I could count eight of them.

- The book opens in a relatively low-key fashion in Brussels. The stealing of a South American tribal fetish is the MacGuffin. It’s disappearance, and the subsequent restoration of a counterfeit in its place prompts Tintin to investigate.

- Hergé then goes on to introduce the main villains Alonso and Ramon as well as Balthazar and his pet parrot. Balthazar is the supposed creator of the counterfeit and has been found dead. Subsequent pages mostly focus on our main characters chasing around the parrot in hopes of finding out who killed Balthazar and took the original fetish.

- This is followed by Alonso, Ramon and Tintin’s adventures on a ship bound for South America. They are after Tortilla, the prime suspect of Balthazar’s murder. Alonso and Ramon dispose him off but are caught by Tintin and handed over to the police.

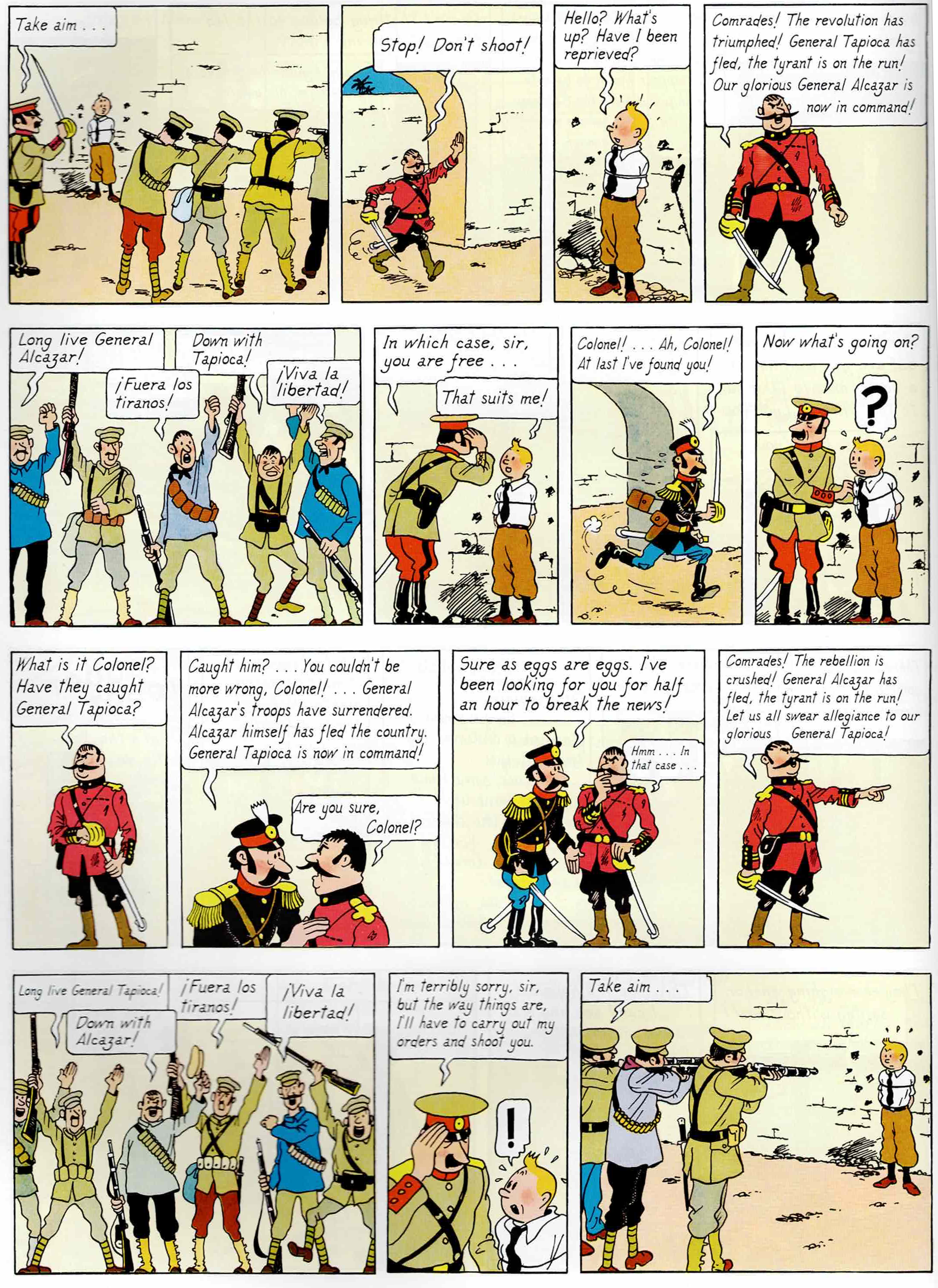

- Tintin is asked to give testimony against the culprits, but it turns out to be a setup. He is caught by the police. He becomes a prisoner of General Tapioca, immediately followed by being a free man under General Alcazar, and again, immediately followed by becoming a prisoner General Tapioca again without moving an inch. The armed police force changes their alliance based on who is in power.

- Tintin is rescued by General Alcazar’s revolutionaries. We are introduced to Alcazar as an egoistical, impressionable and downright incompetent leader. Tintin is appointed a colonel. We are re-introduced to Alonzo and Ramon, who are also caught up in the political turmoil and are part of General Alcazar’s troops. There is a running gag where Diaz, a colonel-demoted-to-corporal tries to kill Tintin and always fails because of his incompetence. In the end, Tintin is imprisoned by General Alcazar for treason.

- Tintin escapes the prison with some help. He is chased by General Alcazar’s troops, gets caught by General Tapioca’s troops again, and is able to escape again. He canoes along River Coliflor and rows into the forests of South America.

- Hergé introduces us to the Arumbaya tribe and their enemies, the Rumbaba tribe. He also introduces a European explorer Ridgewell, who has made the Arumbaya his home. Ridgewell mostly acts as an interpreter in this sub-plot and an exposition device for the story—thus giving some meaning behind the fetish and its materialistic importance in the plot. It turns out that the fetish contained a diamond stolen from the Arumbaya tribe. There is a scuffle between Tintin and Alonzo and Ramon, but neither of the parties claim victory.

- The final arc brings us back to Brussels. Balthazar’s brother has started to make much more accurate replica of the fetish. These replicas are available everywhere. Tintin (as well as Alonso and Ramon) trace down the current owner of the original. A showdown ensues that damages the fetish. Alonso, Ramon and the diamond are lost to the sea. (This is also one of the two Tintin albums where the antagonists die!) The original fetish is all patched up and is placed back in the museum.

Portrayal of a conflict

When the serialisation of The Broken Ear began, Bolivia and Paraguay had just declared ceasefire on Chaco War. The fictional nations of San Theodoros and Nuevo Rico are based on these two countries, respectively.

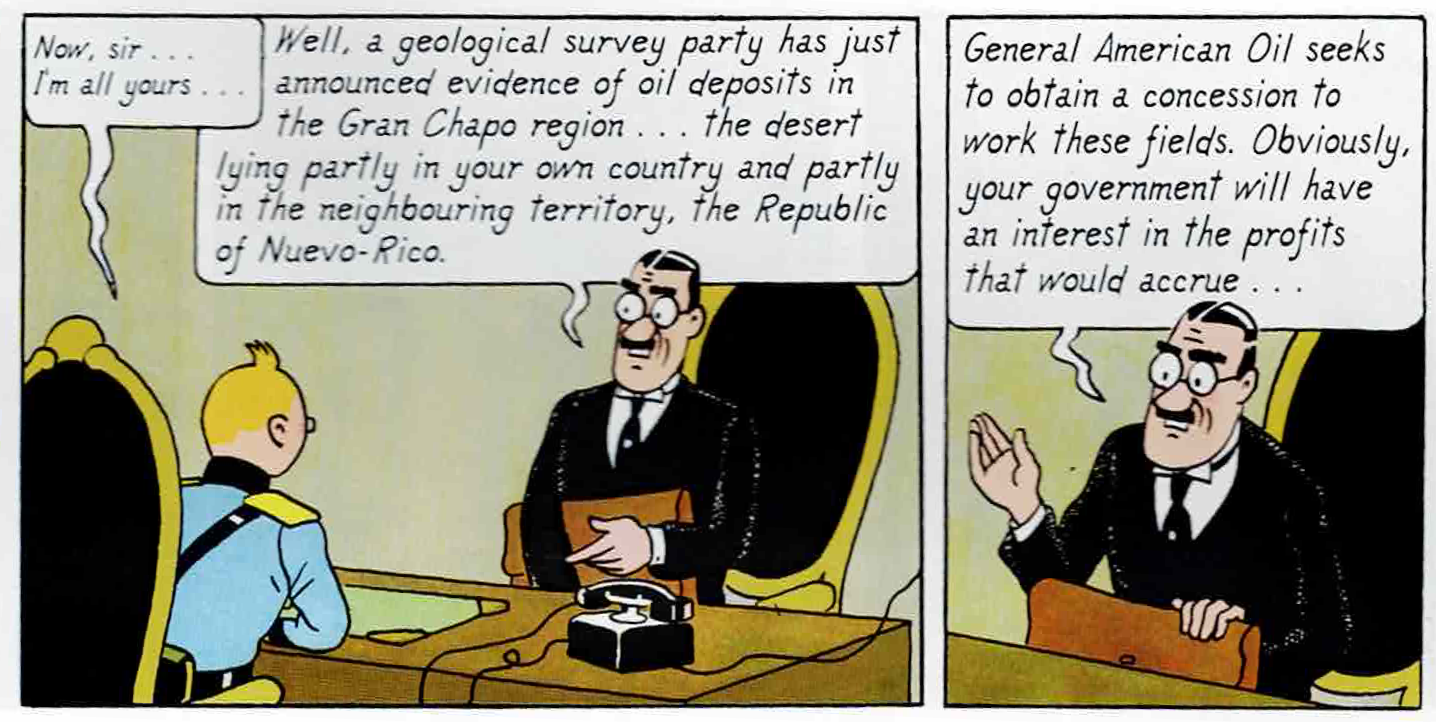

In The Broken Ear, General American oil tries to make a deal for oil in Nuevo-Rican territory. We even see a representative trying to bribe Tintin in exchange for concession over the territory. One of the main triggers of the real Chaco War was the conflict between oil companies who wanted exploration and drilling rights in the Gran Chaco basin; Royal Dutch Shell supported Paraguay, while Standard Oil supported Bolivia. The countries signed a border treaty in 1938 with the majority of Gran Chaco going towards Paraguay—much after the serialisation of The Broken Ear had ended.

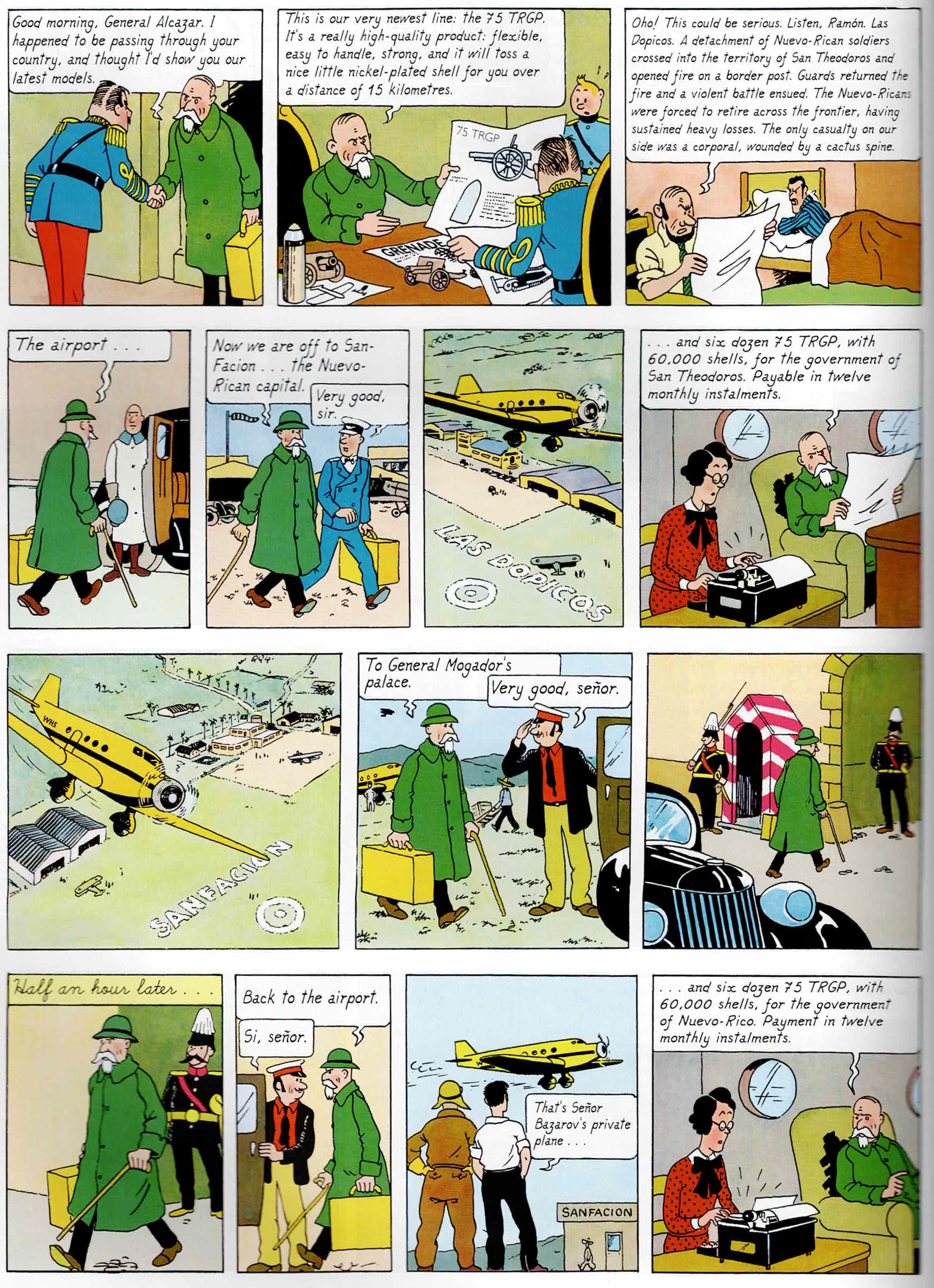

A fictional arms company—Korrupt Arms GmbH—sells weapons to both parties. Hergé doesn’t shy away from satirising our current world where geopolitical conflicts are fuelled by corporations that supply war materials to both parties. Note how Bazarov manages to strike the same deal with both sides of the war. The character Basil Bazarov is modelled after Basil Zaharoff—a Greek arms dealer—who profited by supplying arms to both Paraguay and Bolivia.

The armed police who catch Tintin changes their alliance based on who is in power. This is a caricature, almost a parody of sorts, that shows how those at the lowest level are least bothered about who is in power.

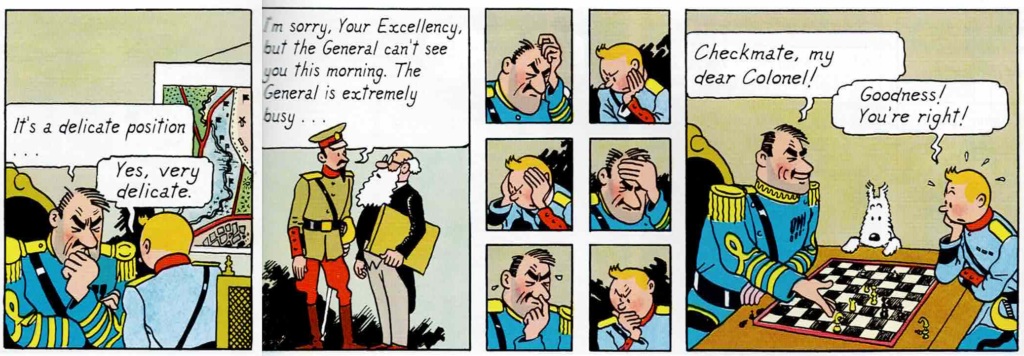

General Alcazar is portrayed as an incompetent and impressionable leader. He prefers playing chess and massaging his ego over managing the actual affairs of the state. Although General Tapioca doesn’t make an appearance, we can almost deduce that he is no better than Alcazar.

The conflict between the two groups would later resurface in Tintin and the Picaros.

Inventing a language

The English translators of the Tintin album—Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner did a fabulous job in translating the “mock” language that the Arumbaya’s spoke. They are basically English phrases—to be precise, Cockney slang broken after every one or to syllables. For example, the phrase, “Ahw wada lu’vali bahn chaco conats!” can be read as “Oh, what a lovely bunch of coconuts! Ha! Ha! Ha!”, and “Goh’ blimeh! Wa’ samma ta, li li li va?… Lem eshohya!” is phonetically equivalent of “Oh, blimey! What’s the matter, lily-livered? Let me show you!”

I have read that in the original French, Hergé used Brusselian dialect of Dutch language. In the Bengali edition, the dialogues are merely transliterated from English to Bengali script, retaining the Cockney pronunciation.

The serialisation of The Broken Ear began on December 5, 1935. (During serialisation, it was not known as The Broken Ear but simply The New Adventures of Tintin and Snowy. That name would be given to the collected edition, published by Casterman two years later.) During this time, Hergé was simultaneously working on The Adventures of Joe, Jet and Jocko that started serialisation in Couers Vaillants on January 19, 1936 as well as Quick and Flupke. This is a testament to Hergé’s work-ethic. This album, along with The Black Island, King Ottokar’s Sceptre make up for the second phase of Tintin comics—marked by plot-driven stories that are rooted in reality. As Le Petit Vingtième folded, so ended Tintin’s solo stint.