"Back in our day…"

We have all heard our parents' generation lament about how 100 rupees was good enough for monthly groceries. Today, we would barely be able to buy groceries for a single day. The same can be said for the future. Maybe in 5 years you will need 200 rupees to buy the same things that you can buy for 100 rupees today. We call that inflation. It is the time value of money with respect to the value associated with the goods and services we purchase from the open market.

Ask yourself some other questions. What is the value of 100 rupees after 5 years if you had kept it in a fixed-deposit? What is the value of 100 rupees after 5 years if you had invested in a business? By how much would the value of a property increase after 5 years? Will it be the same as the increase in prices of furnitures?

There is no verifiable answer to these questions unless you have access to a time machine and have seen the future. We can only analyse the past and make intelligent guesses. Calculating time value of money in various instruments and expense categories will help you take intelligent decisions when it comes to identifying how you should design the distribution of spend, save and give buckets.

How much is the cost of owning a car?

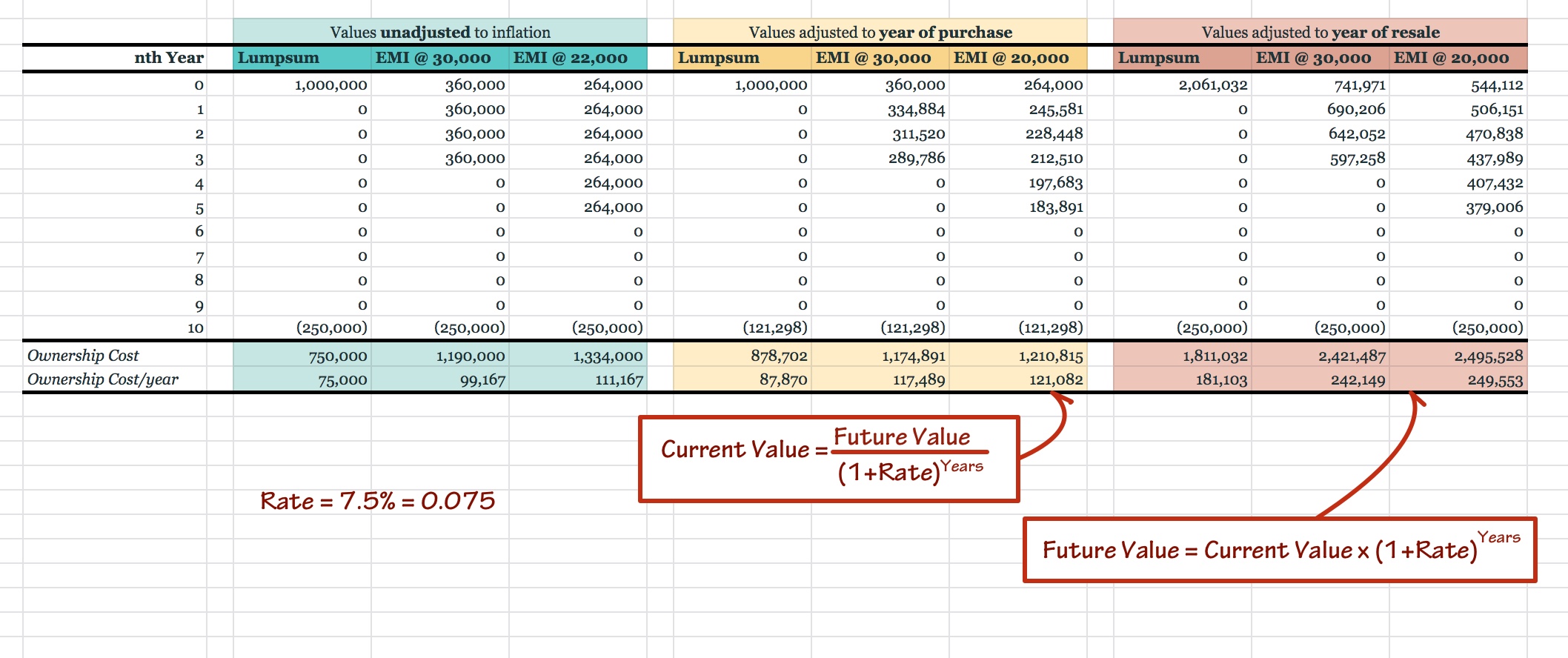

Let us assume that you are eying a car worth 10,00,000 rupees. You have that much money saved up. Out of sheer curiosity, you visit a bank and ask for a loan quotation. The bank gives you two options—20,000 rupees EMI for 72 months or 30,000 rupees for 48 months. You know that you will use the car for 10 years and then sell it for 2,50,000 rupees.

These are transactions that are spread across time. It is difficult to compare today's expense with the same expense 3 years later. It's not a comparison between apples and oranges but definitely between raw mangoes and ripe mangoes. We will have to compute all the costs adjusted to their value at a particular time. Here is how the two computations would look like assuming an inflation rate of 7.5%.

You can either compare your raw mangoes to how your ripe mangoes would have been prior to ripening, or you can consider how your raw mangoes might ripen in due time and compare it to your ripe mangoes. Personally, I am not a big fan of mangoes and I prefer to compute future values adjusted to today. Then again, depending on what analysis I have to perform, I might even choose the other method.

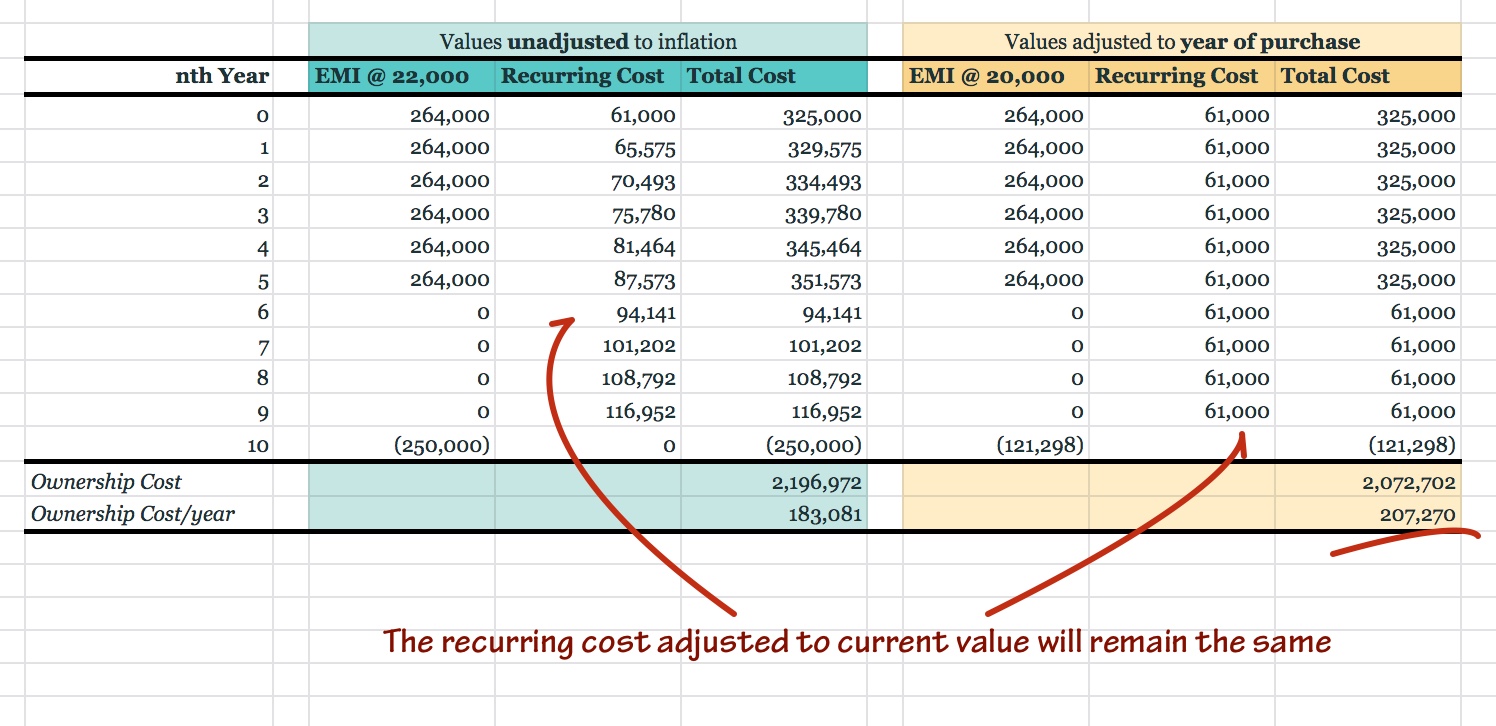

Let us ditch our mangoes and instead consider another aspect of owning a car. Let's say that your car guzzles 3,000 rupees worth of petrol every month. Along with that you have to provision 10,000 rupees for yearly maintenance and some 15,000 rupees to renew your insurance. Note that this value (12 x 3,000 + 10,000 + 15,000 = 61,000) is valid for the current year only. Next year, prices would increase. Assuming that the inflation is the same 7.5%, you will have to shell out 65,575 rupees (= 61,000 * (1 + 0.075)). However, when you adjust it to current value, it will still be 61,000 rupees.

This method can be used to calculate various scenarios, especially many alternatives where you will have to calculate opportunity costs. You will be able to arrive at numbers to help you answers questions like these: Should you buy car A or car B? Should you opt for loan option A or loan option B? Do you really need a new car? Do you really need a car?

Three categories and two thumb rules

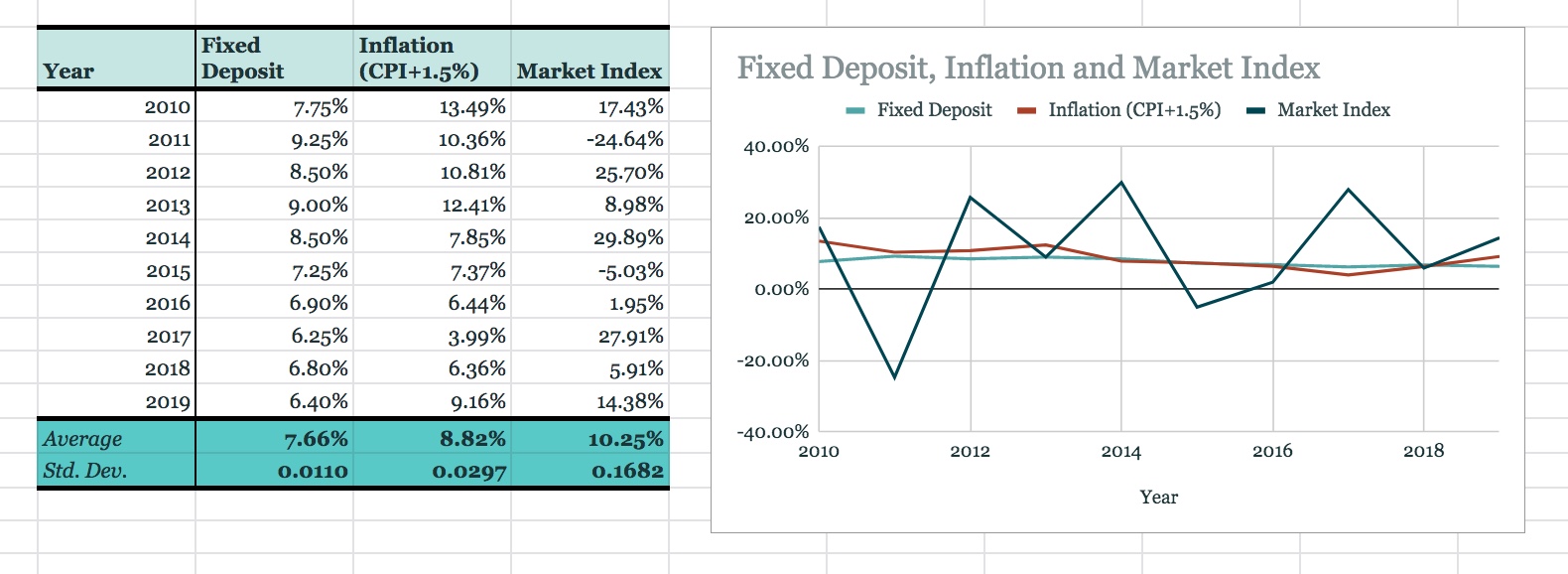

Here is a thumb rule: the returns on debt instruments is less than the rate of inflation, which in turn is less than rate of market growth. This means that the time value of your spend-buckets are sandwiched between the two asset classes of your save-buckets (debt and equity). Have a look at this data—

There is something I would like to mention. It is very difficult to get accurate data for inflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) published in India does not reflect the actual inflation of the prices of items that I used. If you have kept a track of your expenses over a significant period of time, you would be able to compute a far more reliable rate. In my experience of tracking over the last five years, I found that adding anywhere between 1% to 2% on top of the published data gave me the right numbers.

You may come to a conclusion that it is far better to park money in the the market by buying stocks and equity-funds than to put it in fixed-deposits, debt-funds and bonds. So, what's the catch?

Well, there is another thumb rule: the variation (or standard deviation; see the above table) in the returns on debt instruments is less than the variation in the rate of inflation, which in turn is less than the variation in the rate of market growth. This means that if you have parked your money in the market, while the average return might be higher, there is no guarantee that the return would be high for the businesses you have put your money in as there would be large variation of market growth across businesses; or it would be high for the particular year, month, or day on which you would want to encash your money as there would be a large variation of market growth across time.