Accumulation for a lumpsum

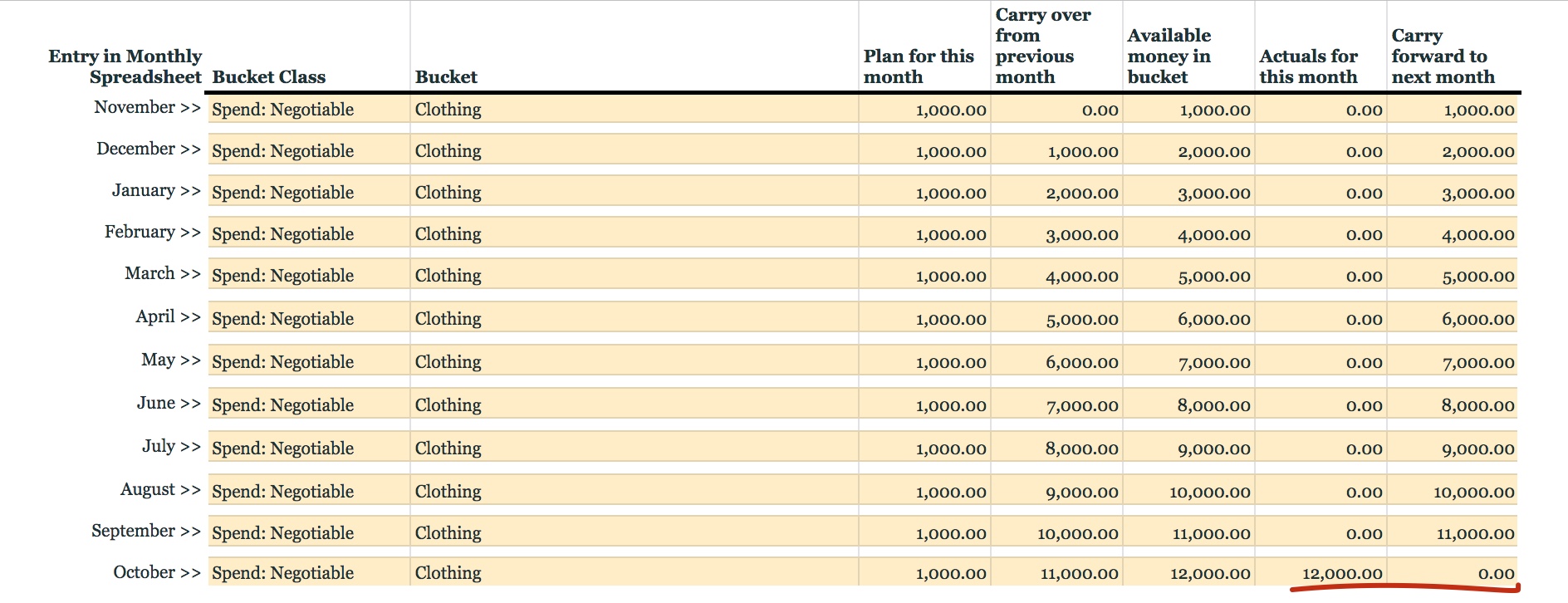

The first case is something we have already touched upon with an example in the previous post—buying clothes during the festive season. There might be other annual lumpsum requirements like insurance premium or a vacation. In most of these cases the budget would be hugely underspent on a month-on-month basis; to the point where the actuals would be zero for most months. We can visualise this using the same example—only that 300 rupees is not enough anymore to buy clothes. So, let's make it 12,000 and chart out a sample plan-bucket-actual scenario for an entire year.

It is important to note that this accumulation must be for a short-term goal. Any goal that is less than two-and-a-half years away can be considered as a short term one. Note how the monthly accumulation from November with no actuals spent increases the available money in the bucket until we are able to spend it all in October.

It is also possible that you might snap your slippers in January and you have to buy a new pair for 100 rupees. It will not be a big deal to accomodate such a mishap. You can either choose to overcompensate for that in your February plan by allocating 1,100 rupees or choose to stick with the usual 1,000 rupees and spend 11,900 rupees on your family's clothing during October. Whichever one you choose, the system will expose your situation well enough to let you take a sensible decision.

Marginal underconsumption in a spend-bucket

In general, if there is an underconsumption in a bucket that doesn't include any large lumpsum payments, there are two things that can be done.

First of all, you can plan a bit less in the next month for that bucket. For example, if you had to spend 4,500 rupees on consumables against an available bucket of 5,000, you would carry the remaining 500 over to the next month. In that case, you will have to allocate only 4,500 next month in your plan to maintain that 5,000 rupees bucket-size. This means that if you have a predictable and regular income, you would have 500 rupees left from your income that can be assigned to a different bucket. Perhaps, you would want to allocate a bit more in the plan towards a save- or a give-bucket.

Alternatively, you may notice that you are constantly underspending that bucket. In such as case, it might be worthwhle to reduce the baseline size of the bucket itself. You will have solid data to compute a new baseline value. Often times I have seen that tracking finances trigger certain behavioural changes. In due time, you will be able to improve the assessment of your "needs" and "wants", which in turn would lead to a reduction of the size of negotiable spend-buckets.

Marginal overconsumption in a spend-bucket

It is not unlikely that there would be some overconsumption in some of the spend-buckets. Just like the previous underconsumption case, you would have to allocate some extra money in the plans for the next month so that the available money in the bucket is back to its baseline. If you are constantly overconsuming, you should re-evaluate the baseline itself.

Let us address another problem. Where did the money for overconsumption come from and what can you do about it?

If you are familiar with production environment or flow in systems engineering, you would have come across a term called slack. Slack is the amount of resources (or stock) you have at your disposal. The more surplus resource you have over and above the operating resource, the more flexibility you will have. This flexibility will not only manifest in your ability to temporarily overspend (such as in this case) but also allow you to transform your budget structure without the real-life suffering of making ends meet while you are going through such a transformation.

There are two ways to account for this. The first one is hidden (at least on this spreadsheet). If you have an emergency pile of cash saved somewhere, you can use that to overspend and compensate with your income at a later date. The second one is transparent. You can deliberately create a bucket with slack built-in. Say, if you spend 5,000 rupees for consumables, you can add a 20% buffer and have a bucket that holds 6,000 rupees at the beginning of every month. On an average you are still expected to spend 5,000 and carry over 1,000 per month. Your planned distribution of income every month stays at 5,000—give or take the amount that compensates for the under or overconsumption in the previous month. You can have different slacks for different buckets as well.

Personally, I prefer the first method. It is far simpler to build a stash of emergency liquid fund (more on that later) and cover any overconsumption. There are two behavioural elements to it, too. Firstly, I like to visualise the current bucket-size as my actual ability to spend at that point. Secondly, I don't have to constantly compute the actual baseline from a number that represents baseline and slack combined all the while filling the actuals to evaluate where I stand at that moment.

An overconsumption that creates debt

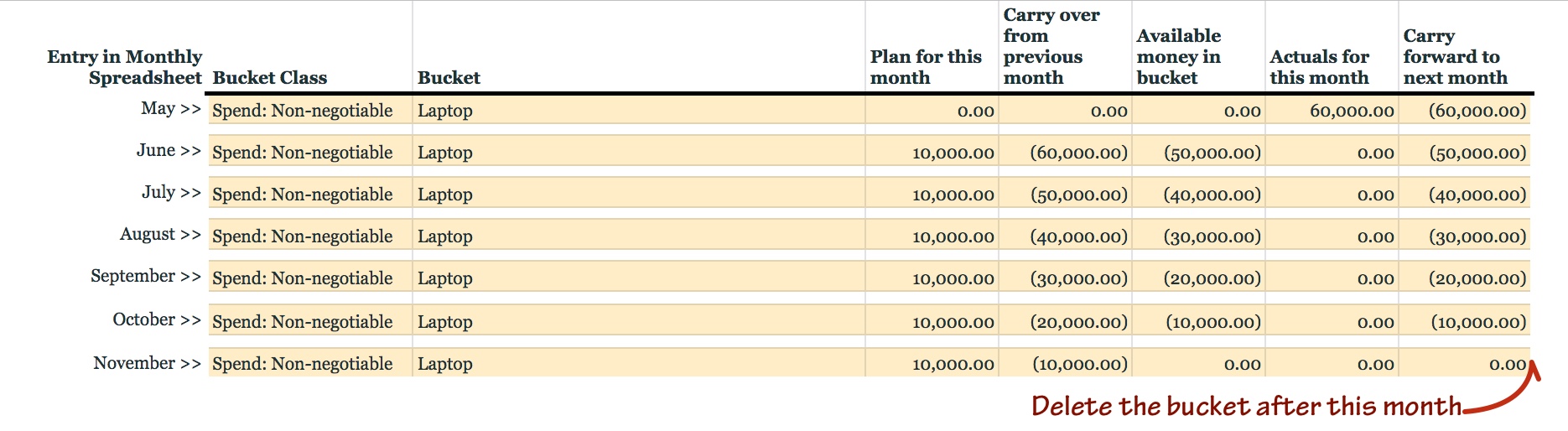

It may so happen that you might have to spend a significant amount of money due to an unforeseen circumstance. Let's say that your laptop—an integral tool tied to your ability to earn—died and you had to shell out 60,000 rupees for a new one. If you have enough money in your emergency fund, you will be able to weather this sudden expense. However, it might not be possible for you to replenish the entire amount in a single month.

Technically, it is a debt. You have borrowed some money from your emergency fund. Since you own the fund, you can give yourself a loan at 0% interest. If you had to borrow from the bank, you would have to pay a lot more than 60,000 rupees. (Not a desirable scenario!)

Note how the loan has created a negative spend-bucket in the spreadsheet. This must be filled in a systematic manner, just like the example above where 10,000 rupees every month is allocated to fill this void for the next six months. This will reset the bucket to zero in a time-bound manner. After this, the spend-bucket can be closed and it need not be present in subsequent months. Needless to say, while allocating money in plans at the beginning of every month, this item should be prioritised. A debt is usually not a good thing—even if it is from your own sources.

I must also mention that such a circumstance need not arise from a misfortune. It could be that you have chanced upon an opportunity to invest in an asset at a lucrative value and you had not provisioned for it.