But first, a lesson from Dave Ramsey

In case you have not heard of Dave Ramsey, he is the person who wrote The Total Money Makeover. He is also the author of the Baby Steps program. Over a period of years, he has helped a number of people get out of debt and sort out their finances; thus establishing himself as a financial advisor guru of sorts.

There are 3 things you can do with money—spend, save and give.

—Dave Ramsey

You might want to read that again. Honestly, I wasn't able to think of a better or a more succinct way of saying it. Although a number of other advisors and bloggers have come up with a larger enumeration, they have merely split these three categories into further subcategories.

In this chapter, we will focus on the first thing you can do with your money—the spend.

Identifying spend-buckets

Planning the spend part requires a bit of diligence. You will need baseline data; you will need to identify spending patterns; you will need some classification of these spending patterns. This brings me to the first exercise you will have to do—

Create spend-buckets and assign a monthly estimate.

This exercise is relatively easy for people who have fully moved to digital payments. If you are one of them, you can scan through your past bank, digital wallet, and card statements and identify spending patterns. Take a printout of the last twelve of your monthly statements and start the exercise. You can do it in a day if you spend enough time. But pragmatically speaking, if you have to work to put food on the table and take care of people and things that are an integral part of life, you can block small chunks of time at night (or whenever it is quite and convenient for you) for a week and finish the exercise.

The exercise would be slightly difficult for people who use cash or use mixed-mode transactions. Unless you have an exceptional memory, there is no easy way but to monitor your spending habits for the next two or three months and arrive at a set of estimates. You will have to monitor the outflow of each and every rupee. Be agnostic to the mode of transaction as well. A rupee spent using your credit card, or via UPI, or a third-party digital wallet, or cash are all the same—it's a rupee. During this period, you might encounter an urge to control your expenditures but please refrain from doing so. Tackling one's finance is as much behavioural science as it is mathematics. By going through this process, you are also identifying your spending patterns that are driven by plans, impulses, or circumstances. When such a situation arise, just do as you would have normally done. It might also be beneficial to make a note of it in a journal. At this point we are only measuring things and not controlling them. Controlling a system with incomplete data or a poorly formed model can only lead to sub-optimal result. The rationale for using three-month data is as follows. There are consumables that are often bought once a quarter. This is especially true if you are living alone. The frequency of replenishment of these consumables is much higher if there are more people in the household. For example, I buy cooking oil once a quarter when I am by myself but I have to buy it every month when my family stays with me. If your frequency of replenishment is high, taking an average of two months would be good enough to create a baseline.

For expenditures that cater to the survival aspect of food, clothing, and shelter, the baseline must be as accurate as possible. You can use a spend-bucket called Consumables that might comprise of grocery, FMCG, and canteen food. You can also have a bucket called Shelter which might include house rent, home loan EMI, home maintenance cost, etc. Other expense buckets can be estimated roughly—like vacation cost, non-essential clothing cost, dining cost, etc. These are expenditures that you might encounter once or twice a year. It is alright to run through old statements and eyeball the values. In the end, chances are that these spend-buckets would not be essential to survival (more on that later).

Here are a couple of examples—

- Consumables (some FMCG items like grocery and toiletries, canteen)

- Shelter (rent, home maintenance, electricity, home insurance)

- Luxury items (some FMCG items like cosmetics, clothing, accessories)

- Eating out (dining, food delivery)

- Car (EMI, petrol, maintenance, insurance)

- Books & Magazine subscriptions

- Internet & Phone

- Entertainment (movies, OTT subscriptions)

- Home asset (furniture, utensils, home electronics)

- Electronics asset (laptop, phone, tablet, accessories)

- Health (doctor, medicine, supplement, annual check-up, medical insurance)

- Education (school, tuition, stationary)

These spend-buckets should be tailored to your lifestyle and spending habits. Add, omit, split, or combine as necessary. A person who isn't into books would not have a spend-bucket called Books & Magazine subscriptions. You might have a hobby like painting; thus, having a spend-bucket called Painting (classes, stationary, paraphernalia) might make more sense to you. Maybe you have a dog as a pet; you might have a spend-bucket called Tommy (food, grooming, vet and medicine). (In my mind, Tommy has always been the quintessential Indian dog.) Maybe, you have a new-born and having something like Baby (doctor, medicine and diaper) might be a rational choice. Maybe it is more pragmatic for you to have a separate spend-bucket called Insurance and track your medical, property and vehicle insurance there instead of the buckets in the aforementioned examples. What matters in the end is that you create these buckets based on what makes sense to you.

Classifying spend-buckets

We can take this idea a step further. The spend-buckets you have come up with must be further classified into "needs" and "wants", or to be semantically correct, non-negotiable and negotiable expenditures. This classification is usually more difficult.

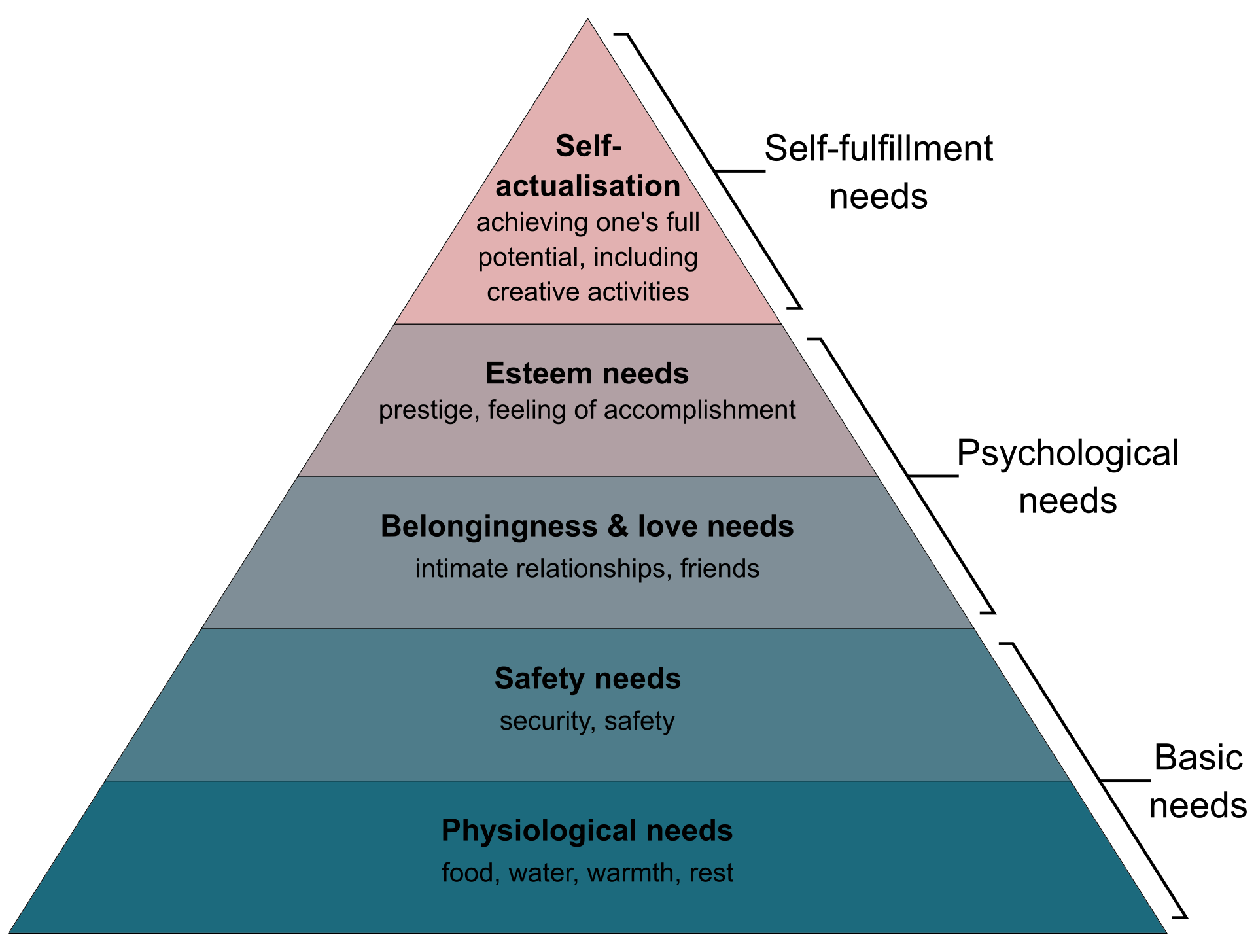

Here is one method that I can suggest. Try to place each of these buckets in one of the five strata of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs pyramid. Physiological needs that comprise of food and shelter, safety needs that comprise of clothing, employment, and health, and perhaps a few social needs like meeting and dining with family and friends might be considered non-negotiable expenditures and the rest can be classified as negotiable. It is possible that two people can have the same buckets but their classifications might be totally different. If your livelihood is dependent on your car—i.e, you are a cab driver, transporter, salesman, etc.—you would classify this spend-bucket in Maslow's safety need strata as it caters to your employment. If you own a car because it represents some achievement in climbing up the social ladder, you would classify it as an esteem need, which automatically classifies as a negotiable expenditure.

It is also possible to ruthlessly classify most of the spend-buckets as negotiable expenditures and classify only those spend-buckets that either physically nourishes you or keeps you from the harm's way as non-negotiable. Jacob Lund Fisher—the author of the blog (and the corresponding book) Early retirement Extreme—suggests such a method. Like all extreme methods, it's not for everyone. But if you consider yourself that ultra-marathoner and can adhere to the rigour and discipline of such a lifestyle, then well, more power to you. By all means, do it the extreme way.

In case of a financial breakdown, knowing what is non-negotiable would come to the rescue. This brings me to the second exercise that you must do—

Classify spend-buckets as negotiable and non-negotiable.

At this point, if you find it hard to classify your spend-buckets because a part of a spend-bucket is negotiable while the other part is not, it would be pragmatic to split that spend-bucket into two spend-buckets such that each of them can be classified without any ambiguity.

Computing survival costs

The summation of your non-negotiable spend-buckets is your current survival cost. This is the cost that would be required for you to survive in case of a financial setback. This value is extremely important when you'll have to plan your future.

I want you to do a mental exercise. Imagine that you have lost every financial asset. Imagine that you no longer have the luxury to afford a life or a lifestyle in your current scenario. Think of extremes and think how would you mitigate that. You might have to live in the outskirts, or maybe in a village. You might have to rely on a public transport to go to work. You might have to survive on basic rice, lentils, and seasonal vegetables. What would be this minimum survival cost of such a lifestyle? This is hypothetical but still I want you to do this exercise—

Compute minimum survival cost and write down the lifestyle associated with it.

There is something I want you to note. These spend-buckets you have created, their classification, and the survival costs you have computed are for today. We have not accounted these values for inflation. If your minimum survival cost today is INR 5000, it wouldn't be so next year. We have also not accounted for any changes in lifestyle. What if you get married, or change cities, or have a kid? All these would change.

Also, I must mention that these are measurement exercises. It is best not to acquire a large asset or a liability or change your lifestyle drastically during this period.